A decade on, here's how Ireland's first austerity budget compares to the 2019 plan

The shift between now and 2009 – when we faced the worst financial crisis in a generation – is stark.

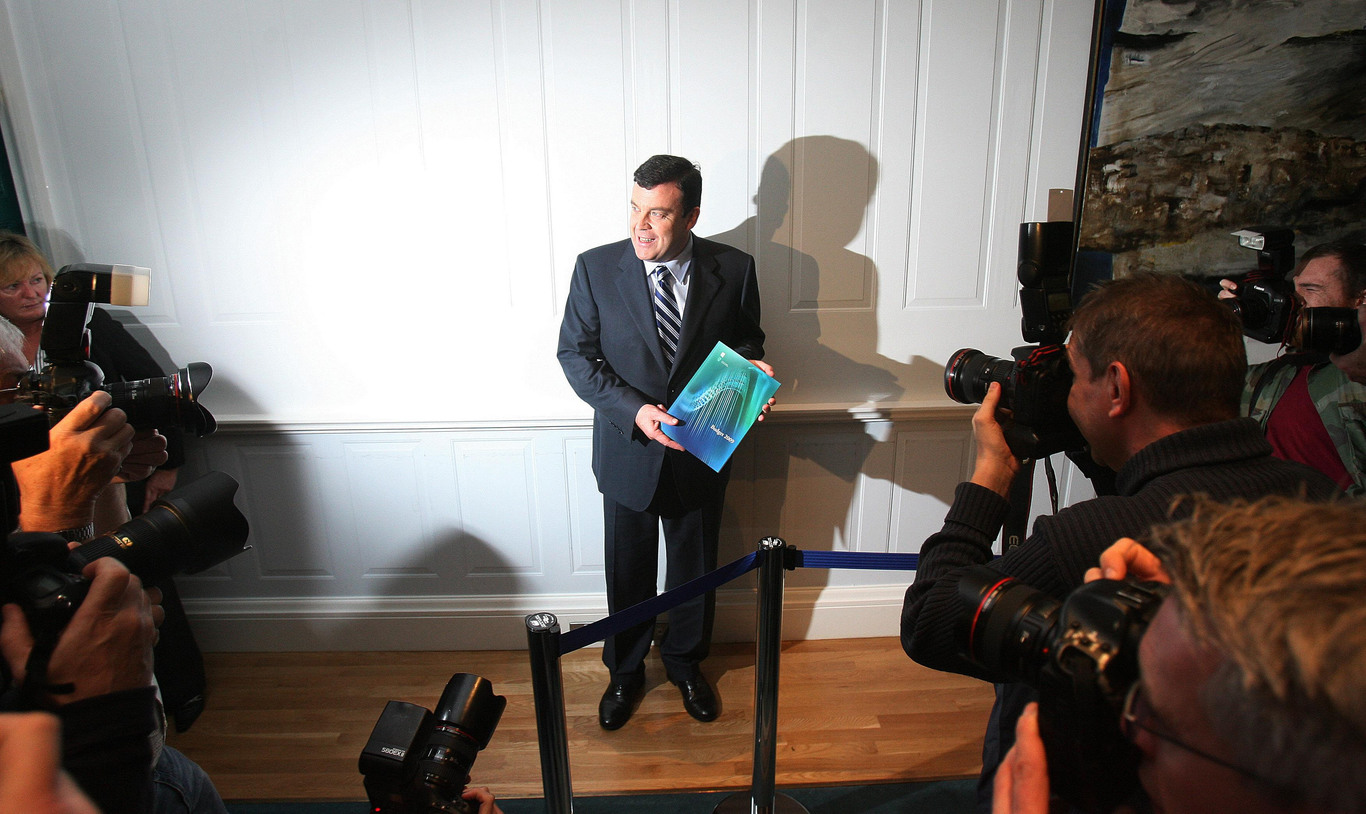

WHEN THE LATE Brian Lenihan addressed the Dáil 10 years ago to deliver Ireland’s first crash-era budget, it’s clear the then-minister for finance knew the eyes of history were watching.

Speaking just two weeks after the night of the infamous bank guarantee, the Fianna Fáil TD didn’t mince his words during his opening statement.

“We find ourselves in one of the most difficult and uncertain times in living memory,” he said.

“Turmoil in the financial markets and steep increases in commodity prices have put enormous pressures on economies throughout the world.

“Here at home, we face the most challenging fiscal and economic position in a generation.”

Ireland found itself in the midst of a global economic decline that threw the world’s financial system into utter chaos and took “even the most pessimistic of commentators by surprise”, as Lenihan said at the time.

Budget 2009 – which was followed by a mini, emergency budget just six months later – was a gloomy affair and marked the start of more than half a decade of hardship.

Brian Lenihan and Brian Cowen

Brian Lenihan and Brian Cowen

Next Tuesday, today’s Minister for Finance, Paschal Donohoe, will stand before the Dáil and present the country’s first Brexit-era budget.

With that in mind, Fora revisits a selection of policies outlined by the government of 2008 – and how they stack up against 2019′s plan.

Tourism taxes

Budget 2009 saw the introduction of the travel tax, which was eventually abolished in 2014.

In keeping with similar moves in the UK and the Netherlands at the time, Brian Cowen’s government rolled out an air travel duty on all departures from Irish airports in a bid to drum up €150 million each year for the State’s coffers.

The measure coincided with a dramatic slowdown in air traffic through Ireland as the financial crisis tore through the economies of both the Republic and its key markets.

The rate was set at €10 per passenger, which was reduced to €2 for shorter journeys. This was later changed to a flat €3 levy in 2011 before finally being axed.

Unsurprisingly, when the levy was first introduced, it enraged many stakeholders in the tourism and transport sector.

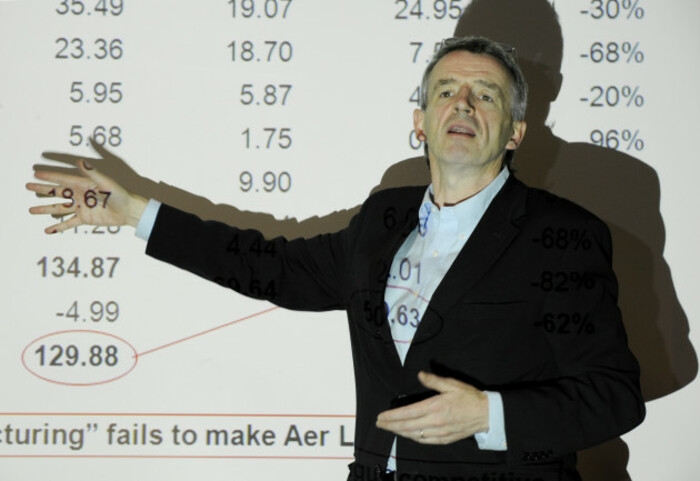

Then majority State-owned Aer Lingus called it anti-consumer, anti-tourism and anti-business, while cost-conscious Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary believed it was “mindlessly stupid”.

Speaking at the National Civil Aviation Development Forum last year, O’Leary described the taxation as one of the “great policy catastrophes” – identifying at the time of the crash that tourism would help pull Ireland out of the recession.

Michael O'Leary (2009)

Michael O'Leary (2009)

Today, tourism is booming and the trade is feeling the heat from another policy that was introduced during the economic downturn – the 9% VAT rate.

A ‘temporary’ measure that was introduced in 2011, it’s highly likely that the levy – which was reduced from 13.5% – will undergo some kind of change in Budget 2019, particularly as hotels rake in record profits.

Minister for Tourism Shane Ross has suggested that a higher rate should be imposed on large hotels, although he hasn’t yet explained how such a system would work.

According to various media reports, his Independent Alliance colleagues are calling for Paschal Donohoe to leave the 9% VAT rate alone.

Despite a strong lobbying effort, it’s rumoured that officials within the Department of Finance are set on hiking the rate to 11%, which could bring in hundreds of millions in extra revenue.

The Irish Tourism Industry Confederation has warned that with Brexit looming, a change to the VAT will disproportionately affect businesses in regional areas that depend more heavily on British visitors.

Its protest has been echoed by the Restaurants Association of Ireland – whose members also benefit from the reduced rate – which recently claimed that increasing the levy by 2% will cost 12,000 jobs if coupled with a so-called hard Brexit.

Housing

With public patience at breaking point, housing is likely to be a big talking point in Budget 2019. The Irish Independent reported that the government is looking to establish a special savings scheme for first-time buyers.

According to the report, aspiring homeowners will be able to open a savings account for their deposit, which will be topped up by the government when they go to buy a house.

There’s also talk of a ‘granny flat grant’ to encourage older people to convert their home into two separate housing units.

Housing Minister Eoghan Murphy and Donohoe

Housing Minister Eoghan Murphy and Donohoe

In 2008, the government of the day hiked the rate of mortgage interest relief for first-time buyers from 20% to 25% for years one and two of their mortgages and to 22.5% for years three, four and five.

To fund the measure, the relief for non-first time buyers was reduced from 20% to 15%.

“This rebalancing makes for a fairer system and helps those buyers with the biggest financial exposure and those facing falling property values,” Lenihan told the Dáil on budget day 2008.

The then-government also committed around €1.66 billion for a range of social and affordable housing schemes.

Income levy

Lenihan introduced a new 1% levy on income of up to €100,100, which rose to 2% beyond that amount. This was in addition to an existing health levy. Both taxes were abolished in 2011 to make way for the much-loathed Universal Social Charge (USC).

It’s unlikely that Donohoe will announce a major overhaul of USC on Tuesday but he might make some minor changes to it to provide lower- and middle-income earners with modest tax cuts in a similar fashion to last year’s tweaks.

Capital Gains Tax

In 2008, the capital gains tax (CGT) was increased from 20% to 22%. Today, the rate is 33%, one of the highest in the western world.

Several professional services bodies have called for Leo Varadkar’s government to bring our CGT closer into line with the UK’s regime, where tax rates on investment gains start at 10%.

In particular, startup and small-business advocates have called on the State to lower taxes on investments in young firms to stimulate the indigenous sector.

These much-hoped-for changes failed to materialise last year, which some commentators dubbed “a real missed opportunity”.

Environment

The bike-to-work scheme was first introduced in Budget 2009 as part of a raft of measures intended to reduce the country’s carbon footprint.

The tax-friendly scheme, which remains in place today, allows employees to purchase bikes and safety equipment worth up to €1,000 through their workplace without having to pay benefit-in-kind tax.

In an effort to make the country greener – and generate some extra income for the Exchequer – it’s expected that Paschal Donohoe will introduce a higher rate of carbon tax on fossil fuels, which is currently set at €20 per tonne.

However, he may increase the weekly fuel allowance of €22.50 to ensure that such a measure doesn’t harm low-income families and older people.

Vices

An old chestnut, smokers are likely to take another hit in Budget 2019, although it’s not clear yet whether Donohoe will repeat last year’s 50c increase on a pack of 20 cigarettes.

Always an easy target, Brian Lenihan slapped a 50c hike on cigarettes in 2009′s budget as well.

Another vice is likely to be on the chopping block this time around: the government is tipped to double the 1% gambling tax to generate €50 million for addiction services for gambling addicts.