'Try hire someone in Silicon Valley without it': How Ireland's share-scheme rules are failing startups

The country’s biggest business group wants tax abolished on staff share options at young firms.

THIS WEEK, IRELAND’S most influential business lobby group, Ibec, launched its pre-budget submission, making several suggestions for improving the landscape for Irish SMEs and startups.

The organisation made a case for loosening tax rules around share options for smaller companies to help them compete with deep-pocketed multinationals in attracting and retaining staff.

Ibec specifically referenced a model in Sweden where share options at smaller companies are exempt from income tax. This applies to companies that are less than 10 years old, have fewer than 50 employees and less than €8 million in revenue.

The idea behind the initiative is to reduce the burden on startups providing incentives to employees.

A share option gives employees the opportunity to acquire shares in a company at an agreed-upon price in the future. When they exercise this option, the employee is responsible for the tax liabilities on their shares.

Ibec director of policy Fergal O’Brien told Fora that share options were a useful tool for indigenous startups, which frequently struggled to attract and retain talent.

“Very often, they simply can’t compete with the salaries that established companies and multinationals are offering, so being able to offer a fairly attractive share ownership package is really important,” he said.

Crucially, according to Ibec, the Swedish scheme has been approved by the European Commission, which deemed that it does not violate state-aid rules.

Fergal O'Brien

Fergal O'Brien

KEEP

In the last budget, the government unveiled its own answer to making share options more attractive as an incentive for staff – the new Key Employee Engagement Programme (KEEP). It sought to relieve some of the burdens around offering share options.

While the government has not published any figures on KEEP uptake, industry insiders soon identified that the long-awaited scheme had fallen short of the mark.

“The feedback we’re getting from members is that it has been very restrictive, the uptake has been very low,” O’Brien said.

Stakeholders have taken issue with some of the caps that the scheme has in place and the fact that it was not retroactive, meaning it could only apply to share options issued from January 2018.

Gill Brennan is chief executive of the Irish ProShare Association (IPSA), which advocates for employee equity in companies. She said KEEP was “not really working the way we would hope it would work”, and a lot of firms were “afraid” to move onto the scheme.

However, rather than scrapping the initiative altogether, IPSA argues KEEP should be used as a “stepping stone” to create a far-reaching scheme that also includes medium-sized enterprises, unlike Ibec’s Swedish-inspired proposal.

“What really struck me about the Swedish piece is that it’s really focused on what would be considered micro or small enterprises,” Brennan said.

“(Ibec’s proposal) is going to discount or exclude medium enterprises that employ more than 50 employees.”

In June, IPSA issued its own pre-budget submission that took umbrage with several aspects of the existing scheme. KEEP currently excludes ‘financial activities’, which can be interpreted as ruling out innovative fintech firms.

It also raised concerns with KEEP’s €3 million limit on the value of share options issued. This, the organisation said, doesn’t jive with growing startups as when the firms take on outside investments it means they could become ineligible for KEEP.

There is also a limit on the amount of share options that can be issued, restricting the value of options to 50% of salary. The organisation also believes the scheme should be open to part-time staff.

“A lot of the SME sector is made up of part-time and temporary staff and we think that KEEP would be an ideal opportunity for SMEs to attract and retain key talent,” Brennan said.

Skirmish for talent

Share options are often seen as one of the most attractive ways for firms to attract and retain talent beyond salaries and traditional benefits.

However Index Ventures, an investment firm based in London and San Francisco that invests both sides of the Atlantic, found that the prevalence of stock options is starkly different in Europe and the US.

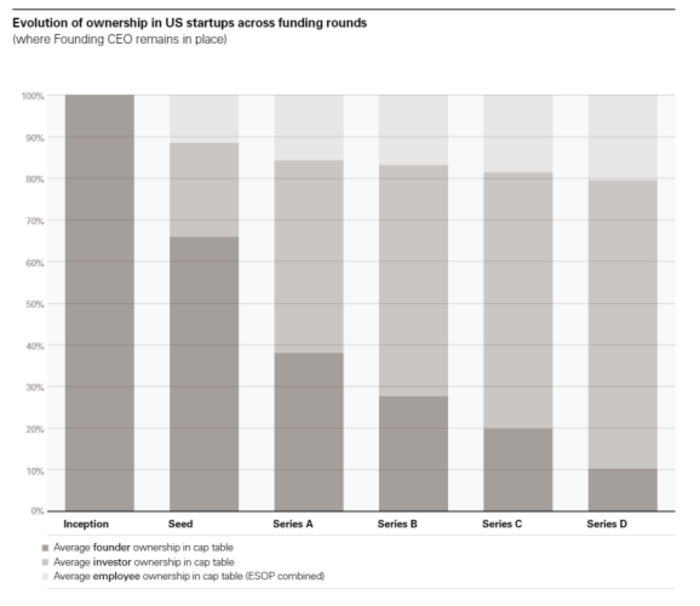

According to its Rewarding Talent research report last year, in the US, employees own an average of 20% of the stock of late-stage startups. In Europe, that figure is around 10% – and is often restricted to only senior-level employees.

“If you want to hire even an office manager in Silicon Valley, they won’t sign on the dotted line until they’ve agreed what the stock option package will be,” Index Ventures’ director of talent, Dominic Jacquesson, explained.

“It’s a core part of compensation, in the same way you wouldn’t dream of joining a company without knowing your salary.”

Jacquesson said that the more advanced an ecosystem, the more likely share options will take off. He pointed to London where there have been several large tech exits, either through acquisitions or stock market listings, where employee shareholders got a windfall.

“That means there are thousands of people who have done very well out of stock options and therefore they become advocates. ‘Hey I did well out of that, I might have taken a lower salary but it paid off’,” he said.

The UK system is more flexible, IPSA’s Brennan added, with higher caps and looser tax rules for the employee.

Startup perspective

London-based co-working space startup Huckletree, co-founded by Irish entrepreneur Andrew Lynch, offers share options to its Irish staff – but only via the UK parent company.

“I think definitely Ireland could benefit from some of those tax incentives that are on the table at the moment because the UK has and as you grow and scale the business, obviously the worth of that equity increases,” Lynch said.

Sarah-Jane Larkin, director general of the Irish Venture Capital Association (IVCA), said that “the KEEP scheme hasn’t been successful in allowing startups to offer share options in a holistic way.”

She added that share options – and an efficient environment in which to issue them – are key to helping SMEs continue growing through access to good talent.

“You are competing at a different vantage if you’re offering a package to an employee and you can’t match the share options offered by an established multinational.”

Waterford startup Fund Recs, which makes fund reconciliation software, has been exploring share options as one way of rewarding its 11 employees and attracting future prospects.

The firm’s chief executive, Alan Meaney, said any share scheme needed to be simple – and work in a way that didn’t put an up-front cash burden on workers.

“Part of the problem now is when you’re interviewing employees and telling them about the share option scheme, you almost need an actuary degree to tell them how that impacts them on a cash basis when they exercise their shares,” he said.

“I think the more you can simplify it, the more adoption you’re going to get.”

‘Sense of frustration’

Ibec’s O’Brien said there was a “sense of frustration” among the business community that more wasn’t being done to support innovative indigenous firms.

“They hear the narrative from government in terms of more supportive policy for startups and entrepreneurship, but it’s not going through in terms of the practicalities of the reform of the taxation system,” he said.

Sarah-Jane Larkin

Sarah-Jane Larkin

Meanwhile, Larkin said that share options are just one area that the government needs to look at to help very early stage companies succeed.

Officials needed to take a “helicopter view” of every scheme and programme, she said, whether it’s KEEP or tax reliefs like the Employment and Investment Incentive (EII) and the Startup Refunds for Entrepreneurs (SURE). The latter two are currently under review by the Department of Finance.

“The economic model in Ireland has been really successful. It’s been based on foreign direct investment and that has made the economy buoyant,” Larkin said.

But proposed changes to EU tax law, as well as Brexit and EU-US trade spats should force Ireland’s hand to improve conditions for early stage indigenous businesses, she added.

“When you look at all of those things looming, I think the Irish economic model over the next number of years is going to come under much more threat than it has before.

“So the viability of support, the safety net that is there for indigenous entrepreneurs who want to set up innovative businesses really needs to be revised holistically.”