The global head of Michelin reveals how restaurants can win a coveted star

There are just 11 businesses in Ireland that have received the esteemed award.

THE INTERNATIONAL DIRECTOR of the Michelin fine dining guide has said that Ireland is on the cusp of a culinary revolution.

Speaking yesterday at the Restaurants Association of Ireland annual conference, Michael Ellis said the food industry here is well-poised to achieve the holy grail of simple food made “sublime”.

“All good food starts with good product – this is a huge asset for Ireland,” he told the roomful of restaurateurs.

“Good ingredients prepared with care. I think this is a huge, huge draw for Ireland, because you can make very, very good food with simple products … That is the hardest thing to do: to make the simple sublime. That is a huge, huge win.”

Ellis – who was born in the US and learned to cook in France – said the country is beginning to develop “a cooking technique” to match the high-quality ingredients produced here.

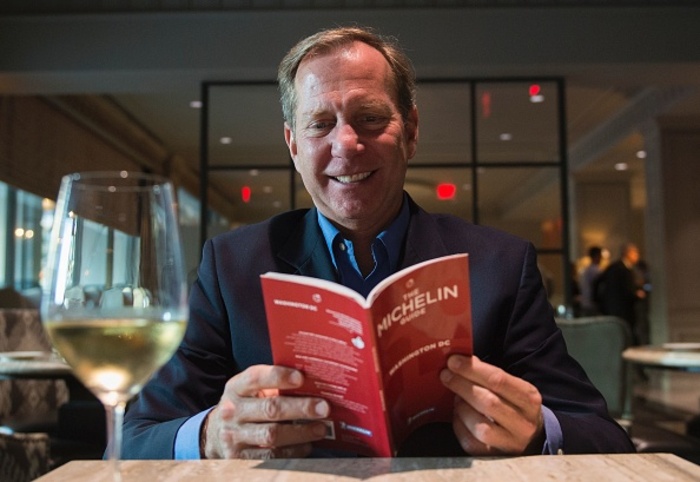

Michael Ellis

Michael Ellis

He said there has been a major culinary revolution in the last five years in particular.

When Ellis first came to Ireland in 1982, he thought the national cuisine was distinctly “overcooked”.

“I’ve been coming here for almost 40 years. I do have memories of having things that were overcooked, whether it was beef or fish,” he said.

Ellis’s view has changed dramatically in the last five years. He said the country has undergone a “huge revolution” similar to the UK.

Three decades ago, modern British cooking didn’t exist, Ellis said, and all the top restaurants in England were run by French restaurateurs despite the high-quality ingredients the country produced.

“They did not have a cooking culture. Now you have British cooks using British products creating their own signatures. That’s happening in Ireland too. I think in terms of snowball, once it gets growing, there’s no stopping it.”

During his address, Ellis explained how the organisation’s highly secretive inspectors decide what restaurants to include in their guides and when to award, or take away, a much-sought-after Michelin star.

More than 20,000 restaurants from around the world feature in Michelin’s guides. Just over 2,500 have a star, 121 of which have achieved the ultimate three-star rating.

There are 11 restaurants in Ireland with at least one star, which means Michelin has deemed it a “go-to restaurant”. Just one - Restaurant Patrick Guilbaud in Dublin city centre – has two stars, meaning the inspectors believe it’s worth going out of your way to visit.

Chef Patrick Guilbaud

Chef Patrick Guilbaud

Other outfits in the Michelin guides either have a Bib Gourmand – a prize for good food at reasonable prices – or a Michelin plate for chefs that serve quality food.

A bugbear for Michelin, according to Ellis, is the fact that the brand seems to be only associated with stars: “We don’t want to be associated only with stars. Unfortunately that’s the only thing anybody talks about.”

For that reason, it is looking at ways to promote the Bib Gourmand and may even rebrand it because so many people find the name difficult to pronounce.

Michelin inspectors

Ellis said all of Michelin’s inspectors are full-time employees and “have the ability to taste and test foods” in the same way that perfumers have a gift for identifying scents.

As a result, Michelin has a difficult time recruiting the right people for the job because it’s up to Mother Nature to decide who has the magic touch, he said.

“You have to have the right number of tastebuds on your tongue to be really able to taste food and translate what’s going on in your palate into the written form. That’s a very, very unique attribute.”

Safeguarding an inspector’s anonymity is also crucial. “If I’m recognised in a restaurant, I get treated differently,” Ellis said, adding that that’s not necessarily a good thing.

“I’ve eaten cold food so many times because of how fussy they were in the kitchen because they wanted to make sure it was good for me,” he said.

When an inspector dines in a restaurant, they look for certain qualities across five broad topics.

They test the ingredients, the quality-to-price ratio, ‘mastery’ of techniques and flavours, consistency on the menu and the “personality of the cuisine”.

“You have to understand what your customers want to eat, how much do they want to pay and what type of environment they want. It sounds very easy, it sounds like common sense, but you’d be surprised at how many chefs don’t do that,” Ellis said.

“Chefs cook what they want to cook, not what their customer wants to eat. Or they do the equation backwards and say, ‘My food costs X, my labour costs Y, my rent is Z, therefore I need a 30% markup and here are my prices.’ That is a dangerous way of doing your business.”

Ellis said restaurateurs should instead consider how much their average customer is willing to pay for a meal and aim to cut costs to meet that target – although that task is easier said than done at a time when the industry is experiencing a shortage of chefs and rising insurance costs.