Britain's craft beer 'gold rush' has slowed to a drip. Here's how the Irish sector is shaping up

Industry pundits warn that more closures are on the way.

THE UK’S BOOM in craft breweries has slowed to a drip as startups battle against multinational drinks makers – and industry pundits say Ireland’s sector is facing similar challenges.

A recent report by British accountancy firm UHY Hacker Young found that eight new microbreweries opened in the UK last year, compared to 390 the year before.

Analysts at the firm say the market is beginning to mature after an initial “gold rush” five years ago and new entrants are finding it increasingly difficult to compete with large-scale producers.

Attracted by the high growth rates and premium pricing that craft beer often commands, multinational drinks companies have introduced their own craft-inspired offshoots – but with the added benefit of big advertising budgets, established distribution networks and existing relationships with retailers and pubs.

Young breweries in Ireland are facing a similar situation as their UK counterparts, according to economic consultant Bernard Feeney, who authored Bord Bia’s 2018 report on the country’s independent microbrewing industry.

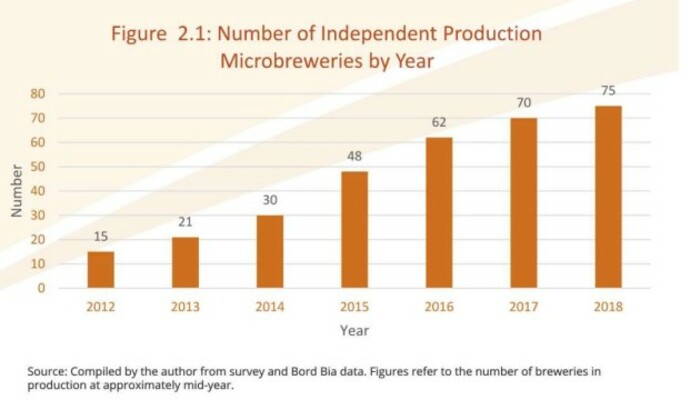

The study last year showed there were 75 microbreweries producing beer by mid-2018, up from 15 in 2012 – but only five up on 2017′s tally, the smallest increase in six years.

“That was quite unusual because we had a situation previously in which you could be getting up to 20-odd new entrants in a year and no closures,” Feeney tells Fora.

“But the situation really changed here up to mid-2018 in the sense that there were 10 entrants but five closures … the first significant closures really to occur (since 2012).”

Click here to view a larger version

Growth in overall production also slowed down, growing by 10.7% in 2017, bringing the total output to some 157,000 hectolitres.

“Actual output from the craft beer sector was only 50% of its total production capacity,” Feeney says.

“So in a situation like that, you’ve got a lot of competition in the marketplace and that undoubtedly has some impact on prices that a craft beer can command.

“People are realising this is not an easy market to enter and obtain a niche as it once was.”

Consumer understanding

Cuilan Loughnane, who owns Tipperary-based White Gypsy Brewery and is a founding member of the Independent Craft Brewers of Ireland group, says the situation of “too many breweries, too little sales” is nothing new and has been recorded in other markets such as Canada.

“This is what happens in gold rushes. Everybody rushes in thinking they’re going to make a fortune. Then they get there and realise that they don’t know where they’re going and the market hasn’t caught up,” he says.

“That has happened in every country that has started out on the craft beer trail.”

One of the biggest challenges Irish craft brewers face is that many consumers don’t distinguish between beers made by multinationals and those produced by independent brewers.

“It’s not like the UK or Germany where they held their beer traditions for a long time,” Loughnane says.

“People like myself had grown up thinking there were just two types of beer. We had no idea that there was ever anything else out there. That’s the base that we’re coming off of.”

Feeney says brands produced by multinationals – for example, Diageo’s Rockshore lager and Heineken’s Cute Hoor ales – have managed to satisfy consumer’s taste for variety.

“Publicans can now offer a range of beer styles and types that obviate the need for a craft beer offer,” he says, adding that some large companies provide pub owners with incentives to stock their brands – as previously reported by Fora - which makes it difficult for cash-strapped microbreweries to access beer taps.

Feeney says Ireland’s microbrewing industry could split into two segments: one made up of a large number of small microbreweries serving local markets, and a small cohort of large microbreweries serving national and export markets.

“It’s unlikely we’ll see again the rate of increase in the number of microbreweries that we saw up until the recent past. What will grow the market will partly be the export market,” he says.

Closures

Loughnane says the cost and difficulty of obtaining a publican’s license means that microbreweries are largely fighting for space on supermarket shelves, where price points are lower and there is a need for a “consistency of supply”.

“What we have seen is a number of small breweries in Ireland investing in larger breweries because they need to bring their prices down,” he says.

He believes France offers the greatest export opportunity for microbreweries because Irish produce has a good reputation there and it is easier to access than other European markets.

But he warns that Irish microbrewers are due to undergo a painful period that will bring about further closures, as witnessed internationally.

“We’re well behind the curve on the US, Sweden, Italy, Denmark (in terms of craft beer market share). But all those countries show the same trend: the initial spike, the slowdown, the straightening out of the curve, the slow ramping up of the curve until you get to 4% (market share). Once you get to 4%, you start to see serious growth.”

Craft brewers in Ireland accounted for 2.8% of the beer market in 2017, according to a Bord Bia report. Loughnane says the figure today is closure to 2.2% and he believes that it will dip over the next 12 to 18 months.

“International trends will show you that you’re going to be in a lull for a couple of years. You will see breweries going to the wall – no doubt about it.

“It’s very tough at the moment because there’s overcapacity. It’s about the good guys hanging in there. From international trends, this is going to grow. Once people get used to drinking a decent beer, they’re not going to go back to drinking macro beers again.”