The one thing holding back the Irish solar industry - and it's not a lack of sun

Developers are queuing up to build the renewable resource in Ireland, but they’re sweating on a subsidy.

WHEN YOUR BUSINESS plan is to build solar farms in a country where it routinely lashes rain in the height of summer, most people would be forgiven for thinking you’re a bit mad.

“When we started on the concept of solar parks in the UK in 2011 we were laughed at,” says Antrim-born Nick Boyle, the founder and chief executive Lightsource Renewable Energy. “Now we have solar parks across the UK and no one is laughing.”

However Boyle’s company, one of the largest solar energy firms in Europe, is just one of several major developers currently eyeing up the Irish market.

At the moment Ireland is one of the few countries in the EU with no commercial solar industry. An estimated total of 1 megawatt (MW), enough to power between 150 and 200 homes for a year, is currently installed across the state.

But this looks set to change in the very near future. ESB Networks, which connects power generators to the national grid, received two solar applications in 2014. Last year there were 329.

Lightsource alone is considering applying for several hundred MW in solar farms, while ESB told Fora there are just under 3,000 MW (or 3 gigawatts) of solar applications already in the pipeline. If even a reasonable fraction of these projects makes it to actually being built, it would represent a big leap into another form of renewable energy for Ireland.

Ireland has no commercial solar farms

Ireland has no commercial solar farms

For developers, there are a few key arguments as to why the country should develop a solar industry – the primary one being the looming prospect of EU regulators slapping Ireland with major penalties.

All member states have signed up to binding renewable energy targets, which in Ireland’s case include having 16% of energy from renewable sources by 2020. If the country undershoots, it could be hit with fines of between €100 million and €150 million for every percentage point it falls short.

David Maguire, the CEO of Dublin-based developer BNRG Renewables and the chairman of the Irish Solar Energy Association (ISEA), says the main push behind solar development is meeting that target.

“Solar can deploy rapidly and it is a light touch on the land. There is a real risk that we won’t meet those aims and solar can deliver a real solution to the government in meeting those targets.”

So if the need and the desire are both there, what’s the hold up? For most developers, the big issue is state support.

“A subsidy needs to be announced,” Solas Éireann director Jason Murphy previously told Fora. The Dublin-based company has announced plans to spend at least €100 million developing solar farms here, but that hinges on government funding.

Both Boyle and Murphy indicated that they felt the same way. But why is a subsidy needed for commercial solar farms, how likely is it to be introduced and how much could it all cost?

A solar farm at Deeside in the UK

A solar farm at Deeside in the UK

Not viable

Simply put, developers say that building large-scale solar farms in Ireland is not commercially viable without some form of state intervention.

Although the cost of solar development has fallen rapidly, this has slowed in recent years. In Europe, that is due in no small part to a minimum import price imposed on solar modules by the EU, which means that developers can’t enjoy the benefit of cheap Chinese imports.

Developers say that the price set by the EU is 20% above market norms, although it is anticipated that the price will be lowered next year and in 2018.

“The modules only make up about 25% of the cost, so even if the price is lowered it won’t make an enormous difference,” Maguire says.

“Because of the nature of solar there were massive cost reductions in the past few years as the technology got more efficient, but those benefits have tailed off.”

BNRG Renewables CEO David Maguire

BNRG Renewables CEO David Maguire

In a submission to the government last year, the ISEA predicted it will cost just under €6 million to develop a 5MW solar farm by 2017, down over 10% on the price at the time. The figure includes a 10% margin, which the association says is lower than that enjoyed by wind developers.

It estimates a typical Irish solar farm of that size could make a net profit of a little over €500,000. However, it assumes that the farm is selling its electricity at a price of 15c/kWh (cents per kilowatt hour) – which is around three times the current wholesale price for power.

Those numbers mean that, as it stands, the farms need to be subsidised if they are going to make their owners any money.

How it could work

There are a few different models for solar subsidies, but the one that the ISEA is pushing for, and the one recommended by KPMG in a report for the industry, is called a contract for difference.

Those contracts ensure a price for a certain unit of electricity. With one in place, the government pays the renewable energy company the difference between a ‘reference’ price – which is based on the average market price for electricity – and an agreed ‘strike’ price.

For example, if a strike price of 15c/kWh is set but the wholesale value of the electricity being produced is only worth half that, the government will pay the developer the difference. If the market price ever goes above the strike price, the renewable energy company is required to pay back the difference. This gives the solar company a very reliable revenue stream.

Maguire recommends implementing a variation on this system in which developers compete for a contract. In this case, an upper limit would be put on the bidding and solar companies could challenge one another for the lowest strike price they would accept. The cheapest, credible developer would win the auction.

Cost and time

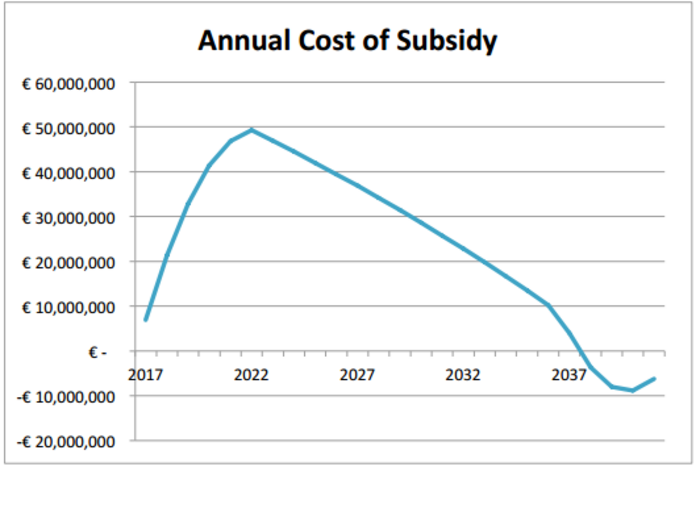

The final cost of any subsidy scheme will hinge on what form it takes. The ISEA estimates that, under an auction system, it will cost an average of €23 million per year over a 20-year period from 2017. At the end of that timeframe, money should start to be returned to the authorities.

Estimated cost of solar subsidy by year

Estimated cost of solar subsidy by year

KPMG’s report puts a higher cost of €60 million per annum on the support mechanism. However, this includes incentives for commercial and residential rooftop, as well as ground-mounted, solar projects.

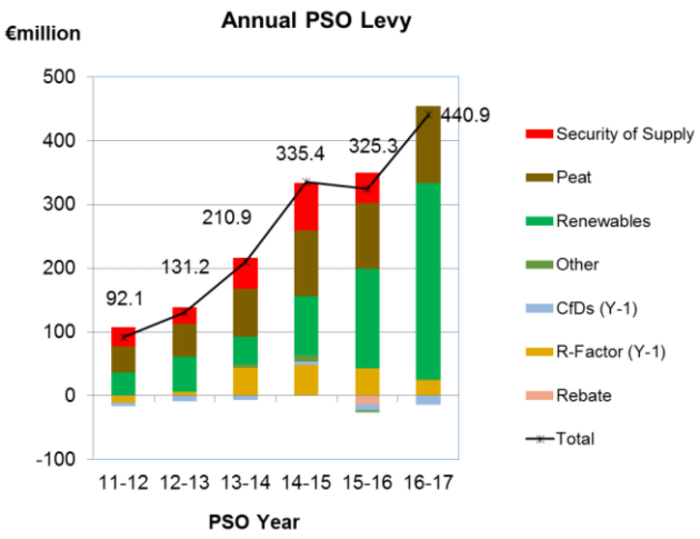

Any subsidy is likely to be drawn from the Public Service Obligation (PSO) levy, a government charge paid by all electricity users which was re-introduced in 2010 to cover the higher costs of peat and renewable energy. It is expected that the levy will take in just over €325 million between 1 October 2015 and the end of September 2016, while yesterday it was recommended the charge be increased another 35%.

Most of the PSO is currently going towards subsidising wind energy. More than half of the levy from 2015/2016 will go towards renewable energy and the vast majority of that is made up of wind subsidies. The total going to renewable sources next year is expected to nearly double again.

Peat energy is expected to receive €122 million in PSO support during 2015/2016 and about €138 million next year.

KPMG estimates that if support for the solar sector, including smaller rooftop systems, is put onto the PSO, it will push up electricity bills for consumers by about 1% a year until 2030. It predicts that ground-mounted projects could become cost competitive between 2025 and 2030.

Behind the curve

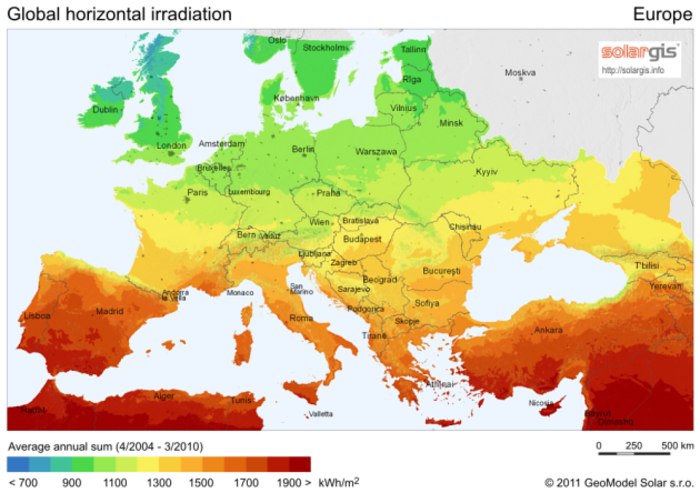

Ireland lags behind much of the Western world when it comes to solar power, despite receiving similar levels of radiation to countries like the UK – which has 8.4 gigawatts (GW) of capacity installed. Many other governments have offered generous tax breaks to get the technology moving and have huge solar industries.

Solar potential in Europe

Solar potential in Europe

In the US, up to $24 billion in federal subsidies have been provided to wind and solar developers between 2008 and 2014, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, and together the two sectors meet about 5% of the country’s electricity demand.

Meanwhile, it is estimated the solar industry received over €14 billion in subsidies in the EU during 2012 – out of a combined €122 billion given to all sources. Coal and onshore wind received the next-highest amounts, at around €10 billion apiece.

The biggest driver of solar development in Europe is Germany, where generous subsidies led to a solar boom. By the end of 2013, it had over 35 GW installed, the most of any country in the world and enough to account for about 6% of electricity consumption. However, the cost of power in the country has remained significantly above that in comparable countries such as France or the US.

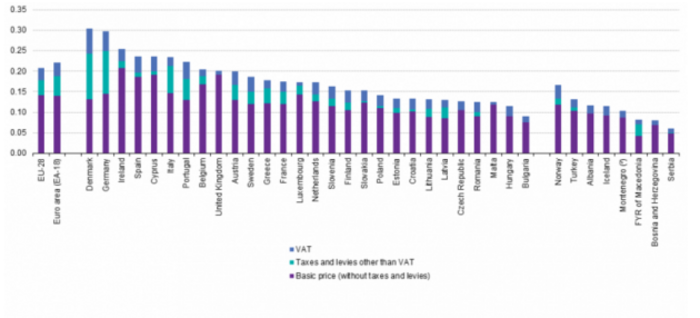

Electricity prices for household consumers

Electricity prices for household consumers

Other countries leading the European solar industry, such as Spain and Italy, generate as much as 7% of their electricity from the sun but are cutting back on subsidies. The UK also recently announced that it was withdrawing support for the solar sector as part of a move to a low-carbon sector that can “stand on its own two feet”.

The critics

Many naysayers, such as economist and UCD professor Colm McCarthy, say that solar should be able to stand alone if it’s to be a viable industry.

“We already have expensive electricity relative to many other countries in Europe, blindly following the EU has landed us with that,” he says. “The shift to wind here has been faster than in most other EU countries, why should each technology have its own target?

“There are idle gas plants, which are a much more efficient source of energy, yet we are looking for subsidies for solar. Why don’t they go away and come back in a few years when costs have fallen? Because they want to make money now.”

Economist Colm McCarthy

Economist Colm McCarthy

Average electricity prices for Irish households are the third-highest in the EU, according to the latest figures from Eurostat, although a relatively small share of that comes from taxes and levies.

Others, such as Eirgrid sustainable power systems manager Jon O’Sullivan, say that solar could be a useful string to add to Ireland’s bow but it’s unlikely that it will be a silver bullet that will solve all of our energy problems.

“Wind farms generate power about a third of the time, but with solar it’s just about 10%,” he says. “You get less energy from solar because it isn’t sunny in winter and you get nothing at night.”

Due to the capacity issue, unless there is a lot of solar installed it won’t make a significant contribution to Ireland’s energy usage. For context, wind energy currently meets about 25% of the country’s electricity demand with an installed capacity of nearly 3GW.

However with the same installed capacity in solar, which is around the amount already subject to applications, the share of total power generation has been put at less than 9%.

O’Sullivan also points out that solar would only ever make a small difference to our overall energy use,. Electricity only consumes about a fifth of our energy needs, with transport making up most of the demand.

“Something like 200MW of solar doesn’t make a jot of a difference to our overall energy needs,” he says.

“That is why I think that it would make sense to incentivise consumers to get panels put on roofs. One or two solar panels is no big issue, but if they were on the majority of Irish household roofs it would make a big difference.”

Solar panels on homes in Japan

Solar panels on homes in Japan

The supporters

While Maguire admits a sizeable amount of solar, “probably 1GW”, needs to be installed to make the industry viable, he adds that the energy would act as a compliment to wind.

“Name me any electricity generation technology that doesn’t benefit from subsidies in some form, whether it’s through tax breaks or policy supplements,” he says.

“Ireland imports 85% of its energy needs; energy security is a big issue and we need to generate more of our own. When the wind isn’t blowing it tends to be sunny and vice versa so there is a great correlation between wind and solar.”

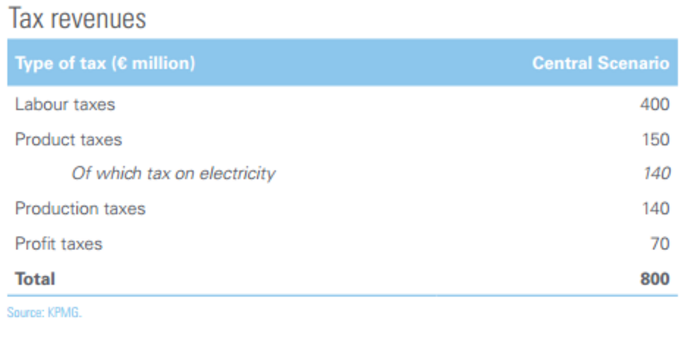

He also pointed to the potential economic impact of the industry. KPMG estimated that the industry could support as many as 7,300 jobs and that activity in the sector could contribute as much as €800 million a year in tax.

KPMG tax estimates

KPMG tax estimates

The chances

Most industry insiders are quietly confident there will be a subsidy announced by the end of the year to come into force in the first half of 2017, although any intervention would still need to clear EU state-aid rules.

Former energy minister Alex White has said several times that the government is looking at the possibility of a solar subsidy.

A spokeswoman for the Department of Energy told Fora that it is increasingly recognised that solar “has the potential to contribute to meeting Ireland’s renewable energy objectives”.

“The programme for government contains a commitment to facilitate the development of solar energy projects,” she said.

“Solar in Ireland is one of the technologies being considered in the context of a new support scheme for renewable electricity generation, which is under development.”

For his part, Lightsource boss Boyle is eager to move in. The UK company just connected the first commercial solar farm on the island, a 4.8MW farm linked to Belfast Airport, but he remains wary of fully committing to a jump across the border until something concrete is in place.

“(We would like) either a mechanism where there is a subsidy centrally delivered from government, or something like Belfast which allows us to deliver electricity directly to a large user – if we are allowed do something similar in the south. I think it’s worth it,” he says.

“There are many international players looking to move into Ireland and Ireland is the only country in Europe without solar, it’s time to get something kick-started.”