How to manage your brand story when the CEO goes rogue

When a PR crisis emerges, it can be very hard to extract a dominant boss from their own mess.

THIS WEEK ELON Musk proved, yet again, that being outspoken and petulant doesn’t mix well with being CEO of a public company.

It raises the very significant question of how should brands manage their story and reputation when their CEO goes rogue.

Musk’s latest Twitter outburst on Tesla has landed him into further hot water with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Tesla – one of the most innovative forces in the electric car market – was controlled by Musk before an IPO in 2010. Once emperor of all, these days he must adhere to the rules of the stock exchange. It’s an understatement to say that this straitjacket considerably chafes his not so delicate temperament.

The compelling stories behind many great businesses are built on the genius, spark, and guile of a dynamic founding CEO. Think of people like Henry Ford, James Dyson, Jo Malone, Phil Knight or Sara Blakely. Their buccaneering spirit, attitude and ingenuity are central to the brands they founded.

This is a positive force when a CEO’s energy is manifested in great products, original ideas and PR coups. But it’s a balancing act.

The very same CEOs can be headstrong, short-fused, ruthless and outspoken. When it all goes wrong it can be very difficult to extract the CEO from their own mess. As the saying goes: “How do you separate the dancer from the dance?”

In short, it’s not easy. But there are a few things that PR and marketing professionals can do to ensure their CEO doesn’t have all the power when it comes to how the brand is perceived by customers.

Dominant CEOs

One key factor in dealing with this reputational conundrum is how your brand is structured and what place the founder or dominant CEO has in the story.

It is no surprise that the Ryanair story is no longer just about Michael O’Leary. There was a time when he was front and centre of every media event, dancing in a leprechaun suit, about to kiss a plane with a big grin on his face, or talking about charging for entry to the toilets on their planes.

But have you noticed this is no longer the case? When is the last time you saw him acting the idiot at a photocall? That’s because Ryanair has worked hard to make their brand about more than just Michael O’Leary.

It had already begun to do this when the company was plunged into the 2017 pilot leave crisis, and had to cancel thousands of flights. If anything this crisis proved to senior management that it was time to move away from O’Leary being the only public face of the airline. The airline has been successful in this strategy so far.

But when your brand is all about your CEO, it can be very hard to weather a crisis; mole hills can very quickly become Mount Everest.

At the time Gerald Ratner gave the keynote address at the 1991 Institute of Directors conference his jewellery company Ratners was recording huge profits. He could do no wrong.

But then in a ham-fisted joke he told delegates the reason they were doing so well was because their products were “total crap”. The reaction was as swift, as it was brutal.

Insulted customers abandoned the brand. The fortunes of the company tanked. Ratner was eventually fired by the board and they went out of business.

Myth

It’s not all bad news. There is a way to link the fortunes of the brand with all that is good about your CEO, without being overly reliant on them.

One great example is the adventure clothes company Patagonia, which was founded by Californian entrepreneur Yvon Chouinard. Patagonia has a simple mission to use business to inspire solutions to the environmental crisis.

It was born out of Chouinard’s passion for climbing and his desire to respect and protect the mountains and cliffs where he exercised his passion.

The Patagonia brand story channels this positive essence every day and has inspired an almost religious-like tribe of believers. That’s when it becomes very powerful.

It’s a similarly positive story with personal care brand Burt’s Bees that still bears the bearded hippy face of its late co-founder Burt Shavitz.

Every day that someone buys one of their natural products, they channel a little bit of Burt’s lifestyle as a hippy beekeeper in rural Maine. This is despite the company changing hands a number of times and now being owned by Clorex, which is best known for manufacturing industrial bleach.

Why does it work? It works because rather than communicating the musings of a volatile CEO, it is almost telling and selling a holistic myth – and it’s one that customers are only too ready to buy.

The ‘Magic Slice’

It’s important to remember that in public companies. the CEO has a role to sell the story to multiple audiences and that they can no longer speak their minds freely.

What might work well on a call with analysts won’t necessarily resonate with customers.

Kingspan – the Irish publicly quoted building materials supplier – performs this balancing act expertly.

Its CEO Gene Murtagh is an excellent communicator who knows how to deliver a message to analysts, while picking his PR opportunities carefully. There is a perfect alignment with its CEO, its business and PR strategy.

The key to having a brand which is ‘CEO resilient’ is to have a defined story strategy. At All Good Tales we work closely with brands to define how they want to tell stories.

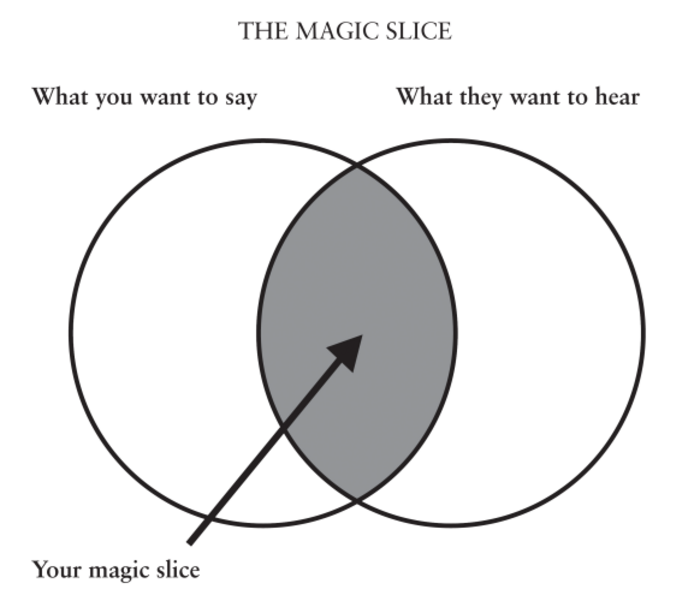

A key part of this process is to define the ‘Magic Slice’ at the heart of their brand. Imagine two circles that intersect where one is what you want to talk about and the other is what people are interested in. Where they overlap is your magic slice of attention.

Click here to view a larger version

Great brands know what this is and they work hard to implement it. It’s never just about their products and it’s seldom about their CEO or founder. They can be a key part of driving the story and their original spark and genius can be part of it, but only part of it.

Jack Murray is the CEO and founder of media intelligence company MediaHQ.com, and storytelling agency All Good Tales.