Why online-only supermarkets haven't come to Ireland... yet

Stock exchange-listed Ocado has global ambitions but hasn’t washed up on these shores.

ACROSS THE IRISH Sea, purely online supermarkets have gobbled up a small – but noticeable – share of the multibillion-pound UK grocery market.

Amazon’s ‘Fresh’ service has grown quickly since launching in Britain two years ago, but it is publicly-listed Ocado – which owns a 1.2% slice of the total market – that has been leading the pack.

The group, founded almost two decades ago by three former Goldman Sachs high-flyers, registered a higher valuation than 150-year-old giant Sainsbury’s for the first time ever last month.

Unlike other supermarkets that sell online, Ocado has no physical stores of its own.

In the UK, it dispatches orders from robot-powered warehouses and has struck up deals to provide such facilities to traditional supermarkets like Morrisons. Similar agreements have been signed with grocery chains in Sweden, France and Canada.

In May, Ocado sold a 5% stake to US food retail colossus Kroger as part of a deal potentially worth over £180 million, depending on the completion of certain sales targets.

Kroger – one of America’s biggest supermarket chains with over 2,700 stores – will have access to Ocado’s technology and infrastructure model so it can provide online shopping to customers using its existing warehouses.

The Irish market

It’s clear that the online-only supermarket has global ambitions, so what’s stopping it from coming to Ireland?

Fora contacted Ocado for comment, but no response had been received at the time of publishing. An industry source with links to the company said the group is famously tight-lipped about its expansion plans.

However, retail experts believe the media-shy group hasn’t yet arrived on these shores for one main reason: the economics don’t quite add up.

“I think it’s probably that the market in Ireland is just very small,” says Linda Ward, a former Marks & Spencer food manager who now owns a consultancy firm called Retail Renewal.

“The smallest markets can be an opportunity if you want to test something, which a lot of companies do use Ireland for. But I think for something like online retail, the whole point is that there’s an economy of scale.”

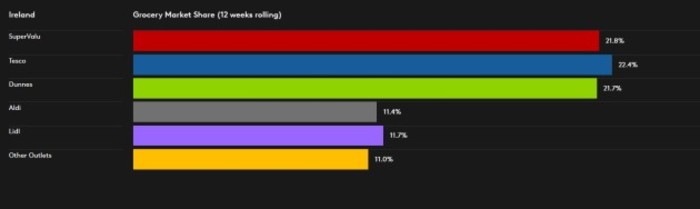

The Irish grocery market, which is worth about €9 billion annually, is dominated by three players that are neck and neck in the market-share wars: Tesco, SuperValu – both of which offer online grocery shopping – and Dunnes Stores.

The two German ‘discounters’, Lidl and Aldi, together make up a fourth force to rival the three largest grocers.

“If an online supermarket were to come to Ireland, they’d be trying to tap into what’s an already small and overcrowded market,” Ward adds.

Click here to view a larger version

Startup third-party service Buymie – which has been backed by retail heavy hitters like Superquinn scion Eamon Quinn – provides on-demand grocery deliveries but takes its stock from bricks and mortar stores.

Logistics

Fraser McKevitt, head of retail and consumer insights at analysts Kantar Worldpanel, says the main barrier to entry for grocers looking to sell online is logistics.

“Fundamentally for retailers, it is less profitable to delve into online that it is to open a store. That is down to what people call ‘final-mile distribution’. It’s just quite expensive to buy a truck and hire someone to drive it to my house at my convenience,” he says.

McKevitt thinks there is an added challenge in Ireland because a larger proportion of the population lives in smaller towns in rural areas compared to in the UK.

“The distances are greater and that just adds to the cost of delivering groceries,” he says.

There are two ways supermarkets can fulfil online orders: they can pick items from existing bricks and mortar outlets or they can operate what the industry calls ‘dark stores’.

“There are, for instance, Tescos (in the UK) that are not open to the public that are basically giant warehouses where they can pick online orders,” McKevitt says.

Dark stores require significant capital investment to build so retailers “have to have enough volume to make it worthwhile”. Ocado’s business operates on the dark stores model, which doesn’t currently exist in Ireland.

That’s not to say the group will never enter the Irish market – McKevitt says he “can’t imagine” why there wouldn’t be sufficient consumer demand for an online-only supermarket.

“The Irish consumer isn’t fundamentally different to the British consumer in that what we want as shoppers is convenience,” he says.

“But what is convenient for me might be different to what’s convenient for you. For some people convenience is the fact that a new micro-supermarket has opened at the end of the road. For other people, convenience is that I can get an app and have my groceries delivered tomorrow.”

The bottom line, McKevitt says, is that retailers have to adhere to the golden rule that applies to all grocery sellers, online and offline:

“Groceries are low-margin, low-value products. How do you do what consumers want – but do it profitably?”