Your crash course in... The long-delayed National Broadband Plan

We take a look back at the many setbacks the project has suffered since it was announced in 2012.

IT’S NOT OFTEN of late that news emerges from the National Broadband Plan camp without the word ‘delay’ somehow connected.

However the talking point was a different one today, when it was revealed the new communications minister, Denis Naughten, had committed to revise the universal service obligation to effectively make broadband speeds of 30Mbps a given right for anyone in Ireland.

He told Silicon Republic that redefining the parameters of the obligation, which currently sets basic copper lines as the bar for telephony services, will be the next step after the rollout of the National Broadband Plan starts next year.

While it sounds like a great idea in principle, four years of false starts on the project suggest any redrawing of the minimum communications standard could still be well over the horizon.

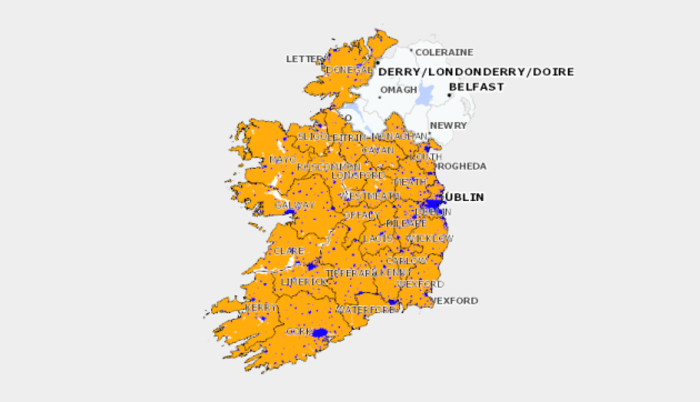

Yellow areas need state intervention for broadband access

Yellow areas need state intervention for broadband access

Click here for a larger version

What is the National Broadband Plan anyway?

Ireland has habitually scored poorly in comparison to other EU countries when it comes to the percentage of households that have access to broadband.

The figures for access to high-speed internet have improved in the past few years, but the outlook was pretty grim in 2012 when then-minister for communications Pat Rabbitte first announced the project.

Back then, only 65% of Irish households had access to broadband, well below the EU average, and the National Broadband Plan – a state-funded intervention for the parts of the country commercial operators wouldn’t touch - was viewed as proactive way of addressing poor connectivity.

However, four years later, work is yet to start and the public remains very much in the dark about the final price tag for delivering high-speed broadband nationwide.

Last September, it was revealed the project will initially be bankrolled to the tune of €275 million, which has been allocated from the capital investment plan, but this will only cover a portion of the cost. The true, unknown expense will be spread over the 25-year lifetime of the project.

Hypothetically, if it all goes as specified, the National Broadband Plan will see 750,000 premises nationwide get a minimum download speed of 30Mbps. This also covers the 30% of Irish businesses that currently have no access to broadband from commercial operators.

Minister for Communications Denis Naughten

Minister for Communications Denis Naughten

So what’s with the delays?

When the government announced the National Broadband Plan in 2012, it was very cagey about putting a time frame on how long the project would take.

With the country in the fits of a deep recession, very little progress was made until 2015, when then-minister for communications Alex White gave hint of hope that things are back on track. He said he expected to be signing contracts with the winning bidder or bidders by mid-2016.

However, even though White hinted that the project was on course again, it again didn’t pan out as hoped. In April of this year, the government announced it had been forced to delay signing any contracts with the winning bidders until next year.

At the time, the further setback was put down to “extensive procurement planning” and a previous deadline extension for companies potentially putting in for the tender.

It has also been confirmed the plan will take up to five years to roll out once the successful bidder has been revealed, pushing the initial 2020 deadline for full completion out to a possible 2022 date.

Former communications minister Alex White

Former communications minister Alex White

Departmental confusion

Looking ahead, there’s one further issue that’s been flagged as having the potential to cause hiccups for the plan.

Unlike in the past when solely the Department of Communications was involved in the process, responsibility is now shared with the Department of Regional Development for overseeing different parts of the scheme.

The government’s logic is communications officials will oversee the procurement process, while the rollout of the infrastructure will come under the wing of regional development bureaucrats to break through any red tape at a county council level that could hamper the project.

The obvious fear is that, after travelling at a glacial pace to this point, the long-awaited broadband project will then be consigned to a progress-destroying interdepartmental wasteland.