The mind behind two of Ireland's most promising startups hopes they'll be sold soon

Inflazome, one of the companies founded by Trinity professor Luke O’Neill, recently raised €15 million.

TRINITY PROFESSOR LUKE O’Neill is hopeful that the two biopharma companies he helped found will be sold in the coming years.

O’Neill, who specialises in inflammation research at Trinity College Dublin, co-founded two of Ireland’s most promising health startups, Opsona and Inflazome.

Opsona was established in 2004 while Inflazome was set up earlier this year.

Inflazome recently raised €15 million in venture capital funding from a variety of sources, including Dublin-based Fountain Healthcare Partners, to help explore new treatments for chronic inflammatory diseases.

Although such raises for early-stage companies would not be uncommon in the US, they are quite rare in Europe and mark out the company as one of Ireland’s most promising startups.

Speaking to Fora at the 2016 BioPharma Ambition Conference in Dublin, O’Neill said he is hopeful that the company would be acquired if it makes it to ‘stage two’ of the testing phase.

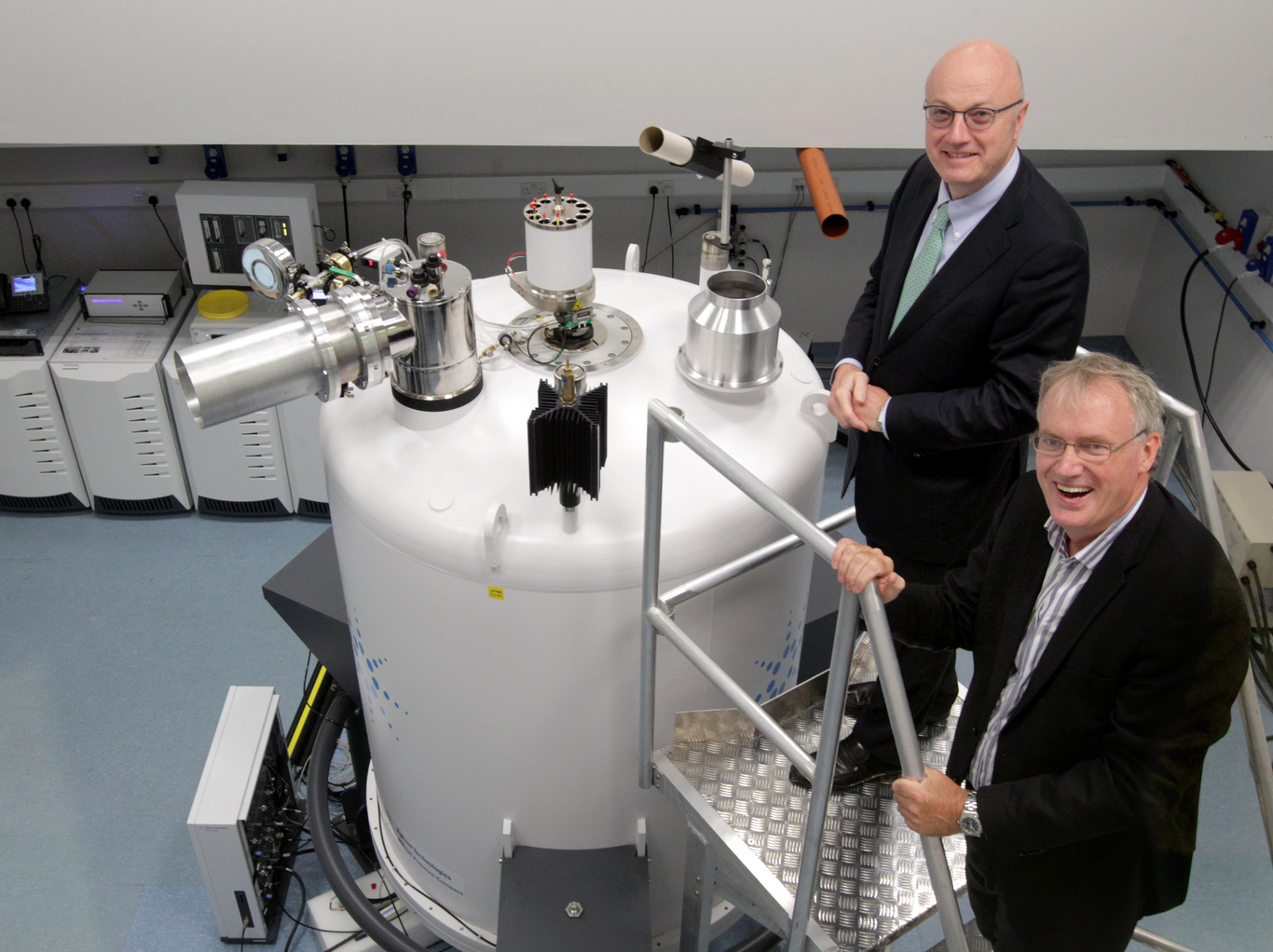

Inflazome founders Matt Cooper (centre left) and Luke O'Neill (centre right)

Inflazome founders Matt Cooper (centre left) and Luke O'Neill (centre right)

Testing stages

Drugs generally go through three stages of trialling before they are finally approved for market.

Broadly speaking, stage one is carried out after preliminary work, such as testing on animals. It is where general safety work checks are carried out.

Stage two involves clinical trials and controlled testing on people while stage three generally consists of much larger, and much more expensive, clinical trials.

It is relatively rare for a drug to pass through the complete second phase of trialling, with a 2011 study finding that about a fifth of drugs make it through the complete stage.

“Your phase two is your first disease group. That’s a small trial usually, it could be 20, 30 patients, sometimes 40, 50 it depends on the disease,” O’Neill said. “That’s the first time you really say, ‘Is this going to work?’

“You get a signal in the phase two and in our case we get bought, hopefully by a big drug company, and they would go to phase three, which is just more patients, and then the drug gets approved.”

Inflazome aims to develop therapies that can control inflammasomes, which are a type of receptor that helps to control how the body reacts to a series of infections.

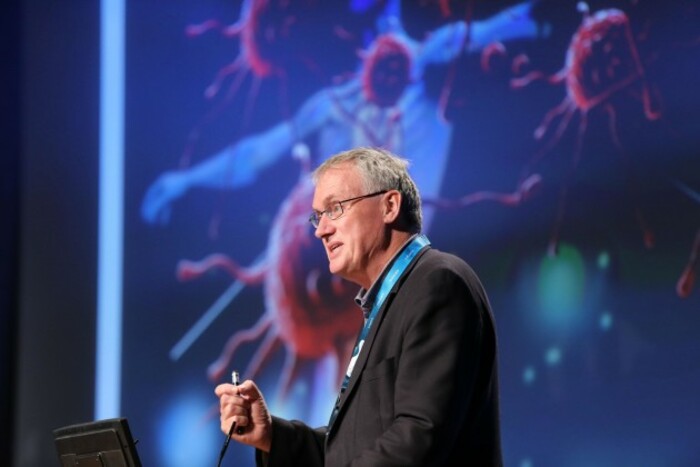

Trinity College professor Luke O'Neill

Trinity College professor Luke O'Neill

Different disorders

However, it is thought that not enough inflammation can lead to persistent infection, while too much can cause chronic or systemic inflammatory diseases.

Inflammasomes have been linked to a host of disorders like gout, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Inflazome is trying to develop drugs that can be taken orally and the company will likely focus on treating one or two conditions.

“We will focus on one disease where it’s easy to do a trial. At the moment we’re exploring which disease to do the proof of concept in,” he said.

Asked when he would hope that the company’s medicines would go to phase one testing, he said: “One to two years, which is a bit quicker than normal. Maybe three to get to the phase two. Three years from the founding of the company to an exit would be fast. The investors would love that (but) it does take time.

“That would be the exit and then the big pharma (company) might take it then. If everything went well our drug could be available in your local pharmacy five years from now.”

Opsona

He also expressed a similar hope for Opsona Therapeutics, a drug development company co-founded by O’Neill in 2004, which is developing a drug to be tested in two different areas, in oncology and as a way to treat complications following kidney transplants.

“We’ve probably spent about €60 million in Opsona. We’re in the clinic, running two trials, they’re in phase two and they’ll be reading out next year,” he said.

“It’s just like Inflazome, if they get a signal in the phase two (that testing is successful), the whole business gets bought by a big pharma and that’s the end of Opsona.

“We thought about an IPO about a year ago but then that window closed so more than likely it’ll be a trade sale. That’d be great (but) you need nerves of steel, you’re waiting with bated breath for the clinical trial results (and) you never know until you see data.”