Food fraud or fair play? The murky business of supermarkets selling 'Irish' seafood

The major chains have adopted similar approaches in marketing fish sourced from abroad.

IN FEBRUARY OF this year, the Advertising Standards Authority of Ireland issued the latest in its regular bulletins on infractions by local businesses.

One of those was a slap on the wrist for German retail giant Lidl, which was found to have marketed fish caught in the Barents Sea, off the Russian coast in the arctic, and off the Namibian coast as being “fresh”.

The industry-funded ASAI duly found that Lidl was in breach of the Code of Standards for Advertising. After Lidl amended the adverts in question, the ASAI concluded that “no further action was required”.

For Irish fishmongers Nicholas Lynch Ltd, which go under the name of Nick’s Fish, the case represented just the tip of the iceberg. Niall Murray, who runs the business with Nick Lynch, made the initial complaint to the ASAI.

“There is a lot more to this problem than just the ASAI issue,” he says.

“The issue of labelling with the Irish flag or keeping the country of origin in the background is happening with pretty much all the big retailers at this stage.”

His campaign for what he argues would be a fairer marketplace began in 2013, when Lidl introduced a labelling system incorporating the Irish tricolour on some of its products.

Then-Lidl Ireland CEO Kenneth McGrath – who has since moved to Denis O’Brien’s Digicel group – told an Oireachtas agriculture committee in May 2013 that “in the absence of clear guidelines, we have developed our own system”.

Nowadays, four years later, using an Irish flag on seafood has become the norm for all the major supermarkets – not to mention brands like Donegal Catch, which can be found in many of the stores.

As far as Murray is concerned, the situation the ASAI adjudicated on in February – as well as further examples detailed below – amounts to food fraud, something the ad watchdog defines as “when food is illegally placed on the market with the intention of deceiving the customer, usually for financial gain”.

However the Food Safety Authority of Ireland does not concur with this opinion.

“It’s impossible to compete with a company like Lidl with its marketing budget, when they are making people believe the product they sell is something totally different to the reality – that is, fresh and Irish,” says Murray.

Here are some examples of the branding in use in Irish supermarkets at present:

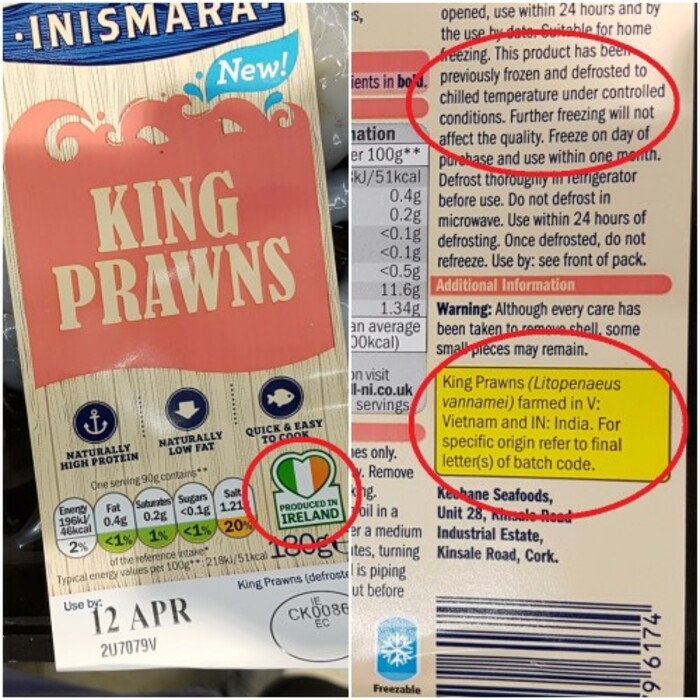

- Lidl – King Prawns bearing the ‘produced in Ireland’ tricolour. The prawns are farmed in Vietnam and India

Click here to view a larger image

- Aldi – The supermarket sells its own Skellig Bay fresh hake fillets branded with a tricolour and a ‘packed in Ireland’ tricolour insignia. The small print says the fish have been caught in the south-east Atlantic and defrosted – which conceivably could mean any waters from Morocco to South Africa. Aldi also sells Skellig Bay tuna steaks, complete with IRFU branding, which are sourced from many different places, including the south-east Pacific

Click here to view a larger image

Click here to view a larger image

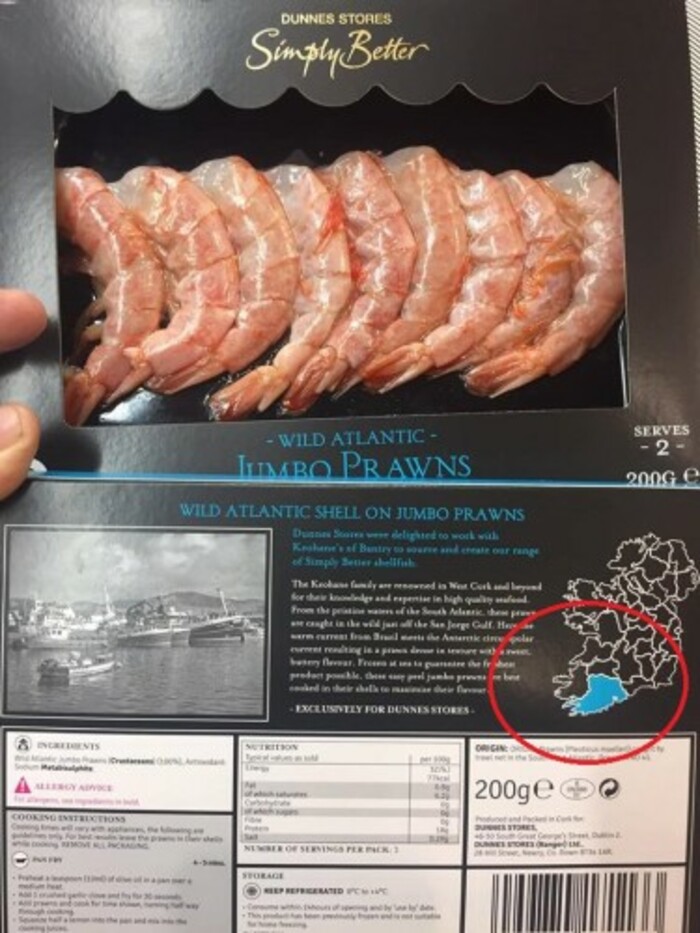

- Dunnes Stores – Sells ‘Wild Atlantic Jumbo Prawns’ with the packaging highlighting Co Cork on a map of Ireland, and true enough this is where the product is packed. The prawns themselves are caught in Brazilian waters, while Nicholas Lynch says he suspects the ‘wild Atlantic’ name may have been picked to evoke images of the Wild Atlantic Way tourist trail.

Click here to view a larger image

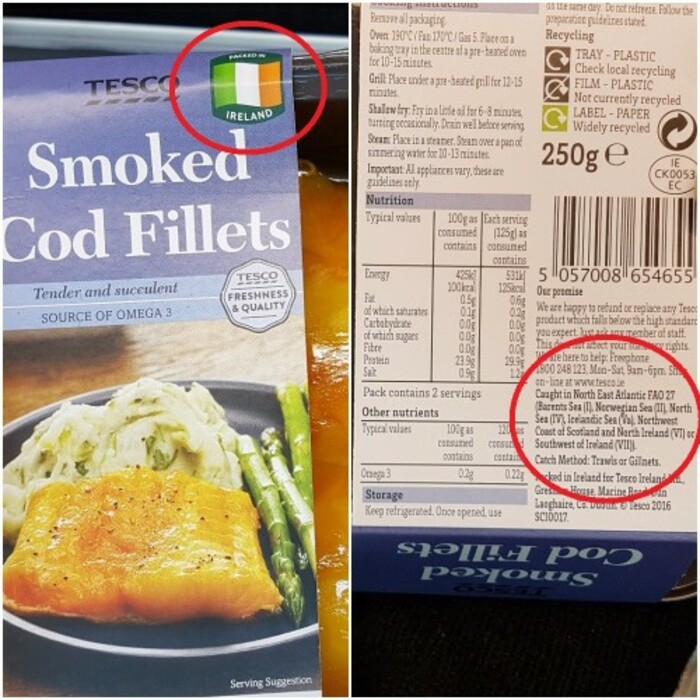

- Tesco – Sells smoked cod fillets with ‘packed in Ireland’ tricolour. The fish is caught in a multitude of places, including off Ireland, but also including the Barents Sea, Norwegian Sea, and Icelandic Sea

Click here to view a larger image

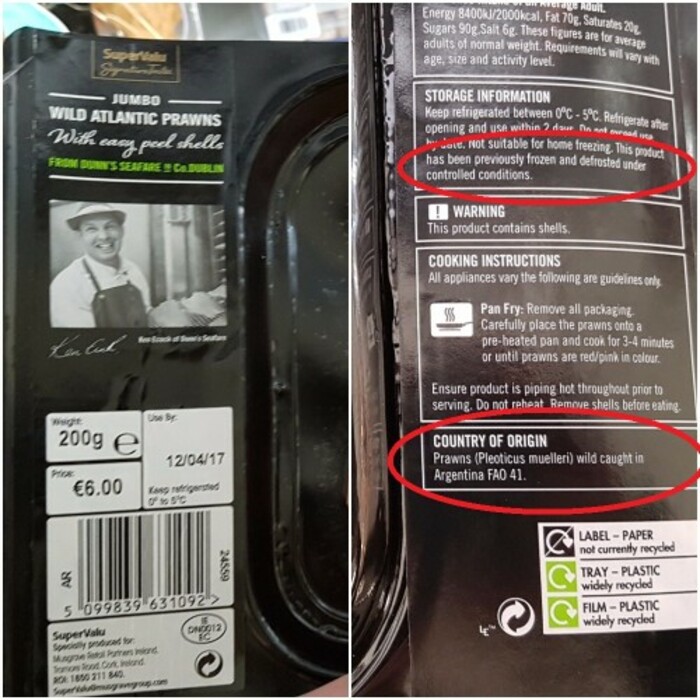

- SuperValu – Also sells Jumbo Wild Atlantic Prawns, labelled as being produced by Dunn’s Seafare in Co Dublin. These prawns are caught in Argentina.

Click here to view a larger image

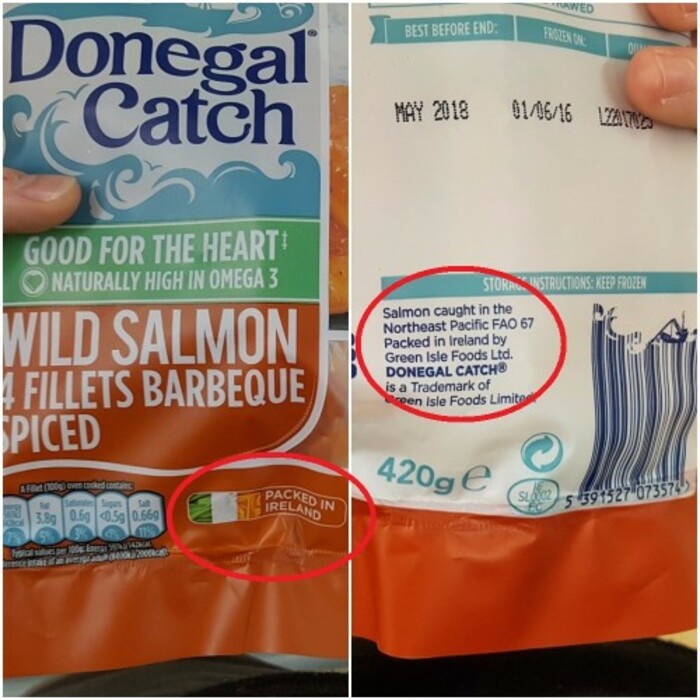

In this example, Green Isle Foods’ Donegal Catch has frozen salmon on sale with a ‘packed in Ireland’ tricolour. The fish, meanwhile, is caught in the north-east Pacific Ocean, which again conceivably could mean in waters anywhere from Alaska to California:

Click here to view a larger image

All this is freely printed on the packaging and Lidl, for instance, has happily admitted in the past that once a product is handled by an Irish supplier, it will apply its ‘product of Ireland’ branding.

So where’s the harm?

Shopping local

The harm, says Murray, is that people want to feel like they’re shopping local – and the supermarkets have realised this.

“It’s akin to the Guaranteed Irish brand when it first came in – it’s sought after,” he says. As far as Nicholas Lynch is concerned, genuine homegrown Irish retailers are losing out as a result.

“For 12 days straight in late 2014 there was dreadful weather in Ireland,” says Lynch.

“We knew there wasn’t a boat in the water fishing mackerel anywhere near Ireland. You can monitor them online, apart from anything else. Yet we had people telling us that ‘there’s tons of it up the road in Lidl, and it’s all Irish’.”

“One way or another that mackerel was defrosted, even if it was Irish. But anyone who wasn’t well-versed in the industry would think they were buying fresh from Cork on the same day.”

For its part, Lidl, as with other large supermarket chains, says its labelling and packaging is “100% compliant with all regulations and all information relating to origin is clearly marked so we are absolutely not attempting to mislead anyone”.

Murray and Lynch have two main bones of contention: that fish frozen at sea thousands of miles away isn’t being clearly marked as having been defrosted, and that an Irish flag is being applied to fish products that are only produced (read, packed) in Ireland.

Comparing recent Lidl brochures for both the Irish and German markets is instructive – in the Irish version, hake, ‘seafood mix’, and cod fillets are all marked as having been ‘produced in Ireland’ with an attendant tricolour.

In the German version, a cod fillet is listed clearly as having been defrosted.

Irish Lidl brochure. Note the Irish tricolour

Irish Lidl brochure. Note the Irish tricolour

March Lidl brochure from Germany showing cod fillet. 'Aufgetaut' translates as defrosted

March Lidl brochure from Germany showing cod fillet. 'Aufgetaut' translates as defrosted

Lidl and Aldi have certainly been a little careless with the rules on occasion. On foot of complaints from Nicholas Lynch, Aldi was outed as selling farmed Scottish smoked salmon as the wild Irish variant last December. It blamed a “descriptive error” for the flaw.

Lidl, meanwhile, was called out for using Bord Bia’s stamp of approval on promotional material advertising its fish. However the food board’s quality-assurance scheme doesn’t cover fish – which comes under the banner of Bord Iascaigh Mhara. That issue was put down to “human error during leaflet design”.

Two weeks after February’s ASAI decision, a Lidl outlet in Co Meath was still stocking the Inis Mara cod fillets under a sales banner reading ‘fresh cod fillets’.

When contacted regarding this, Lidl’s response was: “Following on from the ASAI ruling in February we liaised closely with the FSAI and issued updates in relation to signage and ticketing in all stores. Unfortunately it looks like there was an error with this promotional price ticket and we are reviewing all the ticketing set up internally.”

Inis Mara cod fillets being sold as 'fresh' in Lidl

Inis Mara cod fillets being sold as 'fresh' in Lidl

When we asked all the major supermarkets trading here for their approach to this subject their responses were:

- Tesco: “With regard to Tesco’s own label products, we are fully compliant with all national and European legislation set out with regard to labelling”

- Lidl: “Our packaging is 100% compliant with all regulations and all information relating to origin is clearly marked so we are absolutely not attempting to mislead anyone”

- Aldi: “All products we sell are correctly labelled and comply with all relevant regulations”

- SuperValu: “We rigorously adhere to all labelling legislation relating to the sourcing and marketing of Irish produce”

- Dunnes Stores, as is its custom, did not respond

So, what does the EU have to say? EU Directive 2000/13/EC suggests that “a product … shall be accompanied by particulars as to the … specific treatment which it has undergone (eg powdered, freeze-dried, deep-frozen…) in all cases where omission of such information could create confusion in the mind of the purchaser”.

Meanwhile, Regulation 1169/2011 states that “where a product has been defrosted, the final consumer should be appropriately informed of its condition”.

The FSAI’s take

The ASAI deferred responsibility for our queries to the FSAI when contacted. The FSAI’s response suggests that the matter is not quite so black-and-white as a smaller retailer might believe. A spokesperson told us that the “origin” of wild fish is “not clear-cut”.

Under the EU Common Fisheries Policy ”it is possible for a fish which is not caught in Irish waters, to be considered part of the Irish fish quota”, the food authority said.

“Therefore, on a case-by-case basis, depending on a number of factors as set out broadly above, a fish which is caught outside the Irish territorial waters could still claim ‘Irish’ origin under EU rules.”

Regarding the placement of a national flag on a product, the FSAI’s take is that such practice does not contravene EU legislation.

“The provision of voluntary information on a product label is a commercial decision and whilst the voluntary information provided on a product can differ from one EU member state to another it must always be in compliance with the requirements of FIC (food information for consumers),” it said.

The FSAI also does not take issue with the way in which defrosted produce is being marketed.

All of which suggests that the larger supermarkets are well within their rights to brand their fish products as they do.

But, legally compliant or no, is it misleading? The answer is certainly yes, as far as Murray is concerned.

“The cod I have on my counter today came off a boat called the Adventurer, landed into Ballycotton, and I have to have that off a boat, get it to Ashbourne (in Co Meath), filleted and on my fish counter and sold within 72 hours.

“People might thing this is a case of sour grapes but when you buy from a local fishmonger you support an Irish boat, an Irish boat agent or co-op, Irish processors and an Irish fishmonger.

“The bigger retailers use huge marketing budgets to make consumers believe that these products are the same when in fact they couldn’t be more different, the only thing they have in common is the species is the same.

“The Irish consumer deserves to know what they are buying clearly before they buy it, if something is advertised it needs to be advertised for what it is – defrosted and imported.

“It benchmarks what-should-be-available expectations,” agrees Lynch.

“It’s grossly misleading and simply is not tolerated in other European countries.”

Written by Cianan Brennan and posted on TheJournal.ie