The EU has published 130 pages on why Apple owes Ireland €13bn. Here's what we know.

The Irish government and the EU Commission have been in a war of words.

JUST OVER THREE months ago, a one page statement from the EU Commission sent shockwaves around the globe.

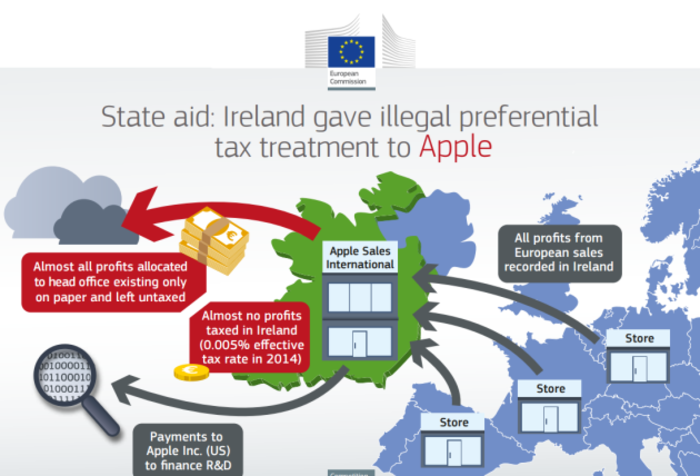

The organisation found that Ireland gave tech giant Apple illegal state aid over a period of more than a decade, and ordered the government to collect €13 billion in unpaid taxes.

After a bit of to-ing and fro-ing, the government decided that it would appeal the decision, and today laid out its full argument as to why it thinks the EU Commission is in the wrong.

That was done to get ahead of the EU Commission, which today finally published its full decision laying out its explanation as to how Apple used Ireland to avoid so much tax.

The EU document is 130 pages long, so we hope you understand that we haven’t had time to go through the whole thing in detail yet, but on first read here are some of the more interesting points:

Apple got a sweet deal:

We knew this anyway, but the main point of contention is whether or not Irish authorities gave Apple favourable treatment and offered it a deal that wasn’t available to most companies.

Apple did not use the notorious ‘double Irish’ loophole to avoid paying taxes. According to the EU the structure it used was similar, but with a few key differences.

With the ‘double Irish’, a business would set up two Irish companies, A and B. Traditionally, A would own the parent company’s intellectual property rights and would be tax resident in a jurisdiction that had nominal or no corporate tax, like Bermuda or the Bahamas.

B would take in all of the parent company’s revenue from Europe, and sometimes locations such as the Middle East and Africa. A would charge B for the use of the parent company’s intellectual property. In this way revenue was sent from B to A, where it would not be liable to be taxed.

The Apple arrangement was similar, but different slightly in that there was only one Irish company involved, Apple Sales International (ASI) being the main one. This company was split into two parts, a local Irish branch and a stateless head office, that wasn’t tax resident anywhere.

ASI holds the rights to use Apple’s intellectual property to sell and to manufacture Apple’s products outside of North and South America. Sales from other EU countries were filtered through the company, which had no physical presence and no employees.

The Irish branch paid a tax on profits. The head office charged the Irish branch for the use of Apple’s intellectual property, so most of the revenue from the Irish branch went to the head office, which was deemed “nonresident” for tax purposes.

According to the EU, Apple asked the Revenue Commissioners if the way it was operating its Irish companies in was ok and Revenue issued two tax rulings, one in 1991 and one in 2007, that allowed Apple’s setup to work for two companies, ASI and Apple Operations Europe (AOE).

The EU argues that this arrangement wasn’t an option for most companies, and that if treated normally, Apple would have been liable to pay its taxes in Ireland.

Revenue Commissioners made deals with other companies:

One of the more interesting points in the ruling is how it questions the decisions made by the Revenue Commissioners.

As part of its investigation, the EU asked Ireland for several tax rulings issued by Revenue to companies with a similar structure to the one set up by Apple, where part of an Irish firm was ‘stateless’.

The Commission said it was unable to identify “any consistent set of rules that generally apply to all non-resident companies operating through a branch in Ireland”.

EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, who spearheaded the Apple investigation

EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, who spearheaded the Apple investigation

“Irish Revenue’s profit allocation ruling practice is too inconsistent to constitute an appropriate reference system against which the contested tax rulings could be examined for determining whether ASI and AOE received a selective advantage as a result of the rulings,” it said.

Apple already settled with Revenue:

For months now, the EU has been publicly pushing for Ireland to collect unpaid taxes from Apple. However, the new documents show that Ireland already did exactly that in 2014, although likely on a much smaller scale to what the EU would have in mind.

The settlement relates to a company called Apple Distribution International (ADI), which was incorporated in Ireland in 2009. From 2012, ADI assumed certain responsibilities for distributing Apple products throughout Europe, the Middle East, Africa and India.

Revenue decided that its 2007 ruling, which allowed Apple to operate its ‘stateless’ companies, did not apply to ADI and made a settlement “for all accounting periods up to and including 2012″.

The exact amount paid was redacted, but ADI made a maximum profit of $240 million between 2009 and 2012, so it wouldn’t have been a figure anywhere near €13 billion.

Ireland repeatedly raised concerns about the EU’s investigation:

Everyone knows that Irish officials didn’t agree with the EU’s decision, but the new papers reveal that they also had major reservations about the investigation as it was being carried out.

The EU Commission’s investigation started in the middle of 2013, and towards the end of 2015 the body was in regular contact with the Irish government.

According to the EU, in December 2015 Ireland sent the EU a letter in which it “expressed its concerns about the manner in which the investigation had proceeded”.

The Irish government formally raised its concerns again and again, with the EU noting: “By letter of 17 February 2016, Ireland again expressed its concerns about the manner in which the investigation had proceeded, indicating that it considered the rules of procedural fairness and the rights of defence to have been breached by the Commission.”

Finance Minister Michael Noonan

Finance Minister Michael Noonan

The Commission said it addressed the concerns in a letter in March, but added: “On 23 March 2016, Ireland sent two letters to the Commission. By its second letter, Ireland again expressed its concerns about the fairness of the procedure.”

The government commissioned a report, without asking the EU:

By the start of 2016, Ireland was obviously very worried about the investigation. So worried that it commissioned a report from PwC, without notifying the EU Commission first. The EU said that the report was “unsolicited”.

According to the EU, the objective of the report “was to provide an opinion concerning the arm’s length nature of the outcome of the allocation of profit to ASI’s and AOE’s Irish branches”.

The EU said: “According to Ireland, (the report) supported its view that the profit attribution to the Irish branches of ASI and AOE endorsed by Irish Revenue in the 1991 and 2007 tax rulings was at arm’s length”.

Arm’s length is a practise of how multinational companies move their money around, in which cash is be shared “between group companies in a way that reflects economic reality”.

The EU generally accepts that companies subscribed to this principle are applying tax laws properly.

Some companies were ‘stateless’, some weren’t

Apple had several Irish companies, but not all of them operated in the same way.

The EU Commission said: “Amongst the companies of the Apple Group incorporated in Ireland, a distinction can be made between companies incorporated in Ireland that are also tax resident in Ireland, such as ADI, and companies that are incorporated in Ireland but are not tax resident in Ireland, such as ASI.”

Apple CEO Tim Cook

Apple CEO Tim Cook

This appears a key point in the EU’s argument that tax ruling granted by Revenue to Apple was selective.

“The Commission considered that advantage to be selective since it is granted only to ASI and AOE and it puts those undertakings in a more favourable position than other undertakings that are in a comparable factual and legal position,” it said.

It also said the profit allocation methods agreed for ASI, Apple’s main Irish company, and AOE, “were considered to result in a remuneration for those Irish branches that a prudent independent operator acting under normal market conditions would not have accepted and thus to deviate from the arm’s length principle”.

How much?

The above reasons led the EU to conclude that Apple’s arrangement with Ireland constituted to illegal state aid.

The Commission said it may confine itself to declaring that there is an obligation to repay the aid at issue, “and leave it to the national authorities to calculate the exact amount of aid to be repaid”.

However, the EU was clear in its statement in August in saying that Ireland must recover “up to €13 billion, plus interest” in unpaid taxes from Apple for the years 2003 to 2014.

Obviously, both Apple and the government have said that the EU is wrong in the substantive part of its argument, and are planning to appeal the decision.

The case will probably be bitterly contested, so this is far from over.