Irish graduates emigrating 'should be regarded as a good thing'

The new head of Trinity Business School says colleges also need to compete in the big ‘blue ocean’.

COLLEGES NEED TO prepare students to work anywhere in the world and emigration should be encouraged not mourned for graduates, according to the new head of Trinity Business School.

The school’s dean, Andrew Burke, told Fora that business had become more “entrepreneurial” with the shift from people holding down the same jobs for years to workers regularly shifting roles.

He said that meant universities like Trinity had to prepare graduates to be “the most flexible and appealing to the job market”, which had already changed from being essentially a local talent pool to a global one.

“I think in general, universities have to prepare graduates to be much more adaptable both in terms of the type of work they’re doing and where they are doing it, because typically a career these days will involve an individual moving across industries, across regions and probably across functions as well,” he said.

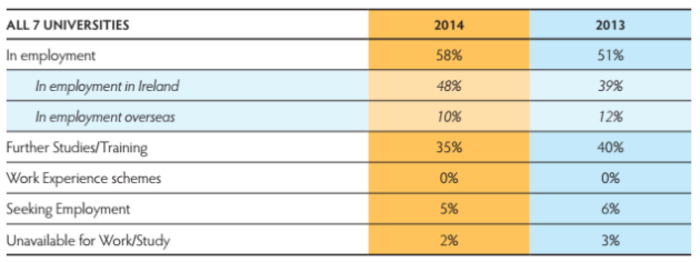

The most recent survey from the Higher Education Authority (HEA) reported fewer graduates from the class of 2014 had emigrated for work than in previous years, down to one in 10 from the latest crop.

However Burke, a Dubliner who took up his post at Trinity last year after spending more than two decades in the UK and US, said he was surprised at the negative reaction to the figure in some quarters with the suggestion that too many educated natives were leaving the country.

“I think in a modern, dynamic, flexible world that shouldn’t be too surprising and it should be regarded as a good thing,” he said.

“People need to pick up expertise, they need to build up their networks and I think having a workforce, based in Ireland, that has a degree of entry and exit into the international market is a good thing and should be encouraged.”

“I think there is still very much this social hangover from the 70s and 80s, and I suppose the recent experience with the downturn, where there was a lot of push effect in terms of people having to emigrate.”

Punching below its weight

The globalisation of the jobs market also has an impact on local colleges, which have to compete with other institutions in both Europe and further afield – an environment in which they have historically underperformed.

Trinity is the highest-ranked Irish college in the respected Times Higher Education rankings, however it comes in at a lowly 78th in Europe on the latest list.

Its major rival in business schools, UCD’s Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School, is the top-ranked Irish business institution in Europe on the Financial Times’ list at 36th.

Trinity doesn’t even feature in the top 85 for those scores, although it performs better in the Eduniversal Deans’ Ranking marks – where it takes top billing in Ireland and is placed 15th in western Europe.

Burke, who was speaking ahead of the Trinity Global Business Forum today, has been vocal about the country’s business schools failing to reach their potential and he readily admits Trinity has been ”punching below its weight” in the field.

“I think that demand in the marketplace has changed the whole industry, because I think in the past if you look at business schools and indeed universities they essentially could survive on their local markets,” he said.

“That’s changed from a situation where these universities could survive and thrive and survive in a small pond to a situation where they need to survive and thrive in a blue ocean.”

Trinity Business School dean Andrew Burke

Trinity Business School dean Andrew Burke

With that in mind, Trinity has been changing its approach from being a “boutique provider” to a full-suite business school with global clout, he said. Last year the college was granted permission to build a €70 million complex to house the school, a project it aims to have finished in mid-2018.

Trinity also unveiled its LaunchBox business incubator in 2013, while Burke said it was “well down the track” to doubling student numbers and tripling the faculty size in the business school.

“First and foremost, the one thing any student wants is a degree that carries clout in the labour market,” he said.

“They want to be able to pitch up in Melbourne or Los Angeles or even Moscow for that matter and have a degree which the organisation that is looking at it is not only aware of the where they’ve got the degree but knows how good it is. So really that’s placed a huge onus on any business school to have a strong international reputation.”