Streaming giants are cornering the entertainment industry - what's in it for Ireland?

With Apple, Disney and HBO entering the game, there’s more opportunity and competition than ever.

JOHN RICE, CHIEF executive of Jam Media, remembers how hard it once was to get the attention of big American studios when pitching ideas for TV shows. With the rise of streaming giants globally, that’s no longer the case.

The company produces content for the BBC, Netflix – and Amazon, having signed a deal with the Jeff Bezos-fronted giant to produce a preschool-age show for its streaming service.

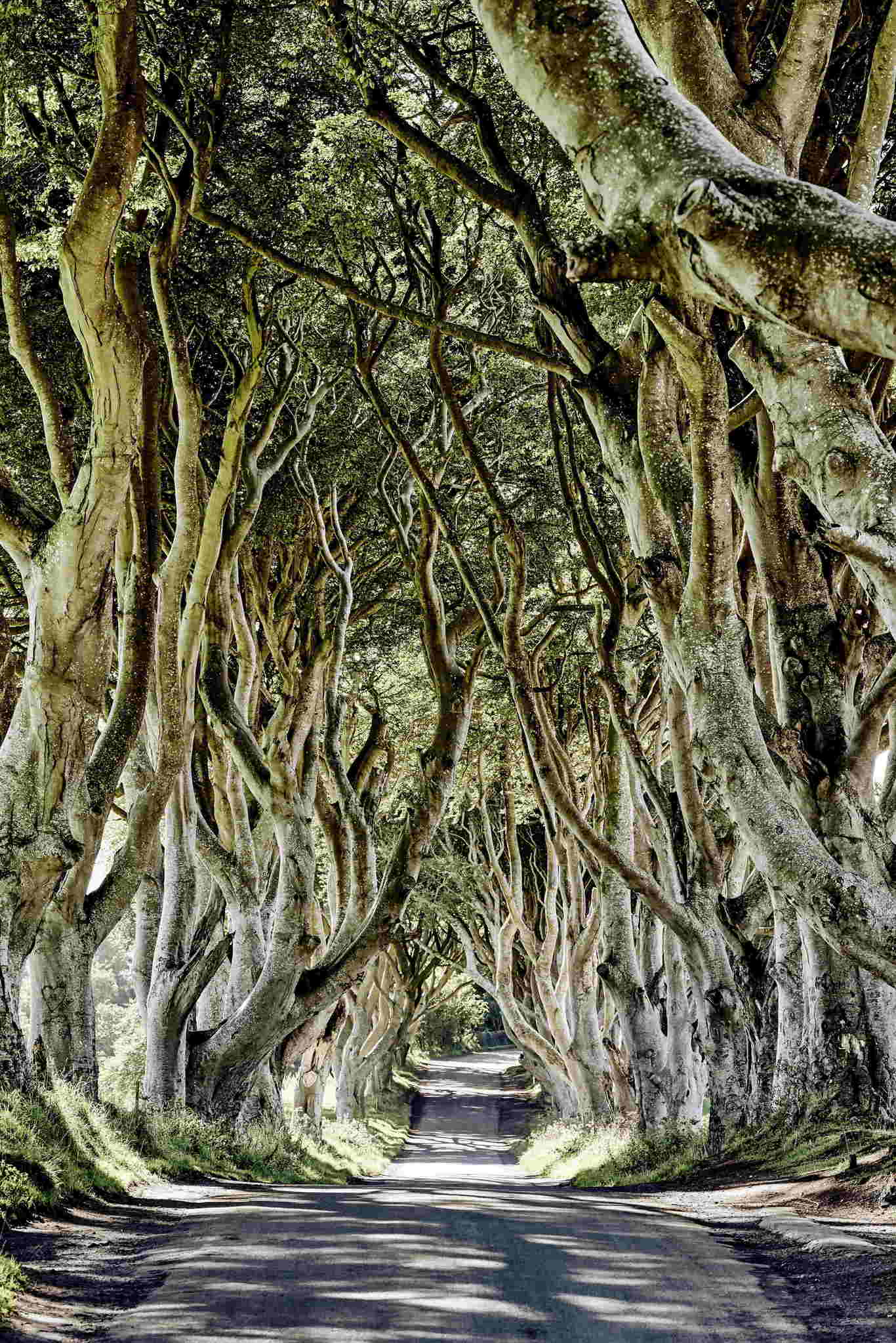

As streaming giants corner the entertainment market, more opportunities are becoming available. On the back of success stories like Game of Thrones, Penny Dreadful and Vikings, Ireland has made its name as a destination for both filming and production.

“I think there’s a real openness on the part of streamers to work with international companies. Part of that reason is because often more than half of their subscribers are outside of the US so they have to look for other voices internationally,” says Rice.

That openness is spilling over into traditional networks, he says, because the international content is working so well for streamers.

John Gleeson, head of accounting firm Saffery Champness’s Dublin office, believes the increase in activity from streaming giants has “trickled down significantly to Ireland”.

For example, it has been reported that Limerick-based Troy Studios is to begin filming for sci-fi series Foundation and to debut on Apple TV+, the tech behemoth’s new on-demand streaming service.

Meantime, Disney announced in April that it will be producing a show called Disney Villains for its rival service. Production on the series is due to begin in late 2020 at Ardmore Studios in Wicklow.

A still from Jam Media show 'Becca's Bunch'

A still from Jam Media show 'Becca's Bunch'

Increasing competition

The streaming market is increasingly crowded. In addition to Amazon, Apple and Disney entering the arena, WarnerMedia’s HBO Max will also start jostling for market share.

“There’s a real excitement, even though at the moment it seems like the sands are shifting quite rapidly as the new players come,” says Rice.

These companies behave similarly to traditional broadcasters commissioning content from studios.

They’re also “well capitalised”, according to Gleeson, “because they are competing in an environment where existing studios are moving to have online streaming services”. This is likely to result in increased competition for content acquisition and production.

“The more efficient model for anyone who’s acquiring intellectual property is to try and commission the production of content rather than try and acquire it when it’s been a breakout success for another network,” says Gleeson.

With more places to pitch to, there is more money available for content producers from streamers and “more likelihood of getting a piece of intellectual property into production”, Gleeson adds.

Similarly, Rice says the opportunities for established companies and newbies are “huge”. But he adds that government supports and tax reliefs need to remain.

“If they were to go, I think we would be in a very different place,” he says, noting that labour costs are lower elsewhere and other countries are also “tinkering with their tax regimes”.

Section 481 is a tax break intended to promote investment in Irish film and television productions. The relief, the rate of which is 32%, was recently given European Commission approval to continue until 2024.

The launch of Netflix in Ireland (2012)

The launch of Netflix in Ireland (2012)

Rising to the challenge

Gleeson suggests that the opportunity exists across various categories, from animation to live action.

“We’ve seen a lot of TV production for streaming and animation for television as well. But if you look at what Netflix and Amazon are doing, they are absolutely in the space of commissioning feature films as well,” he says.

Earlier this week Netflix announced that it would forgo a theatrical release for Martin Scorsese’s upcoming film The Irishman and will debut it on the streaming service. The company bought the film – first mooted in 2008 – from production company Fabrica de Cine and agreed to finance its climbing budget.

In the model of the future, Gleeson thinks cable television will be usurped by a multitude of streaming sites. He doesn’t yet know where TV will sit in that mix.

The Irishman, he says, is a good indication that streamers like Netflix are “upping the ante”.

Dublin-based television production company COCO Content – maker of the Irish version of First Dates – had its debut foray into streaming with the 2017 documentary The 34th on Netflix.

Managing director Stuart Switzer takes a more cautious approach to the rise of the streaming industry and the Irish potential to rise to the challenge.

He believes the structure of the Irish broadcasting sector needs to be reimagined “for the independent sector to really take advantage of the opportunities”.

Unpaid licence fees and the rise of streaming giants over traditional television mean it can be hard for Irish producers to grow to the necessary scale to compete internationally, he says.

“If these streamers are starting to take over the world, which they are, the content we produce as a small nation is important,” he says.

“We’ve got to convince them that we have the wherewithal. It’s the ability, the track record and the funding. We can’t get the track record … unless we have more work domestically to get the scale to divert funds into dedicated development.”

Compared to international players, Ireland’s industry – though successful – is small, Switzer says.

“The ability and the ambition is here but the budgets aren’t.

“With more money we can make programmes with bigger budgets which will look bright and shiny and attract the streamers more than saying, ‘That’s what we made. We could do it better if we had more money.’”

Note: An earlier version of this article stated that Troy studios had announced its involvement in the filming of Foundation and a budget of €45 million. The studio did not make this announcement.

Get our Daily Briefing with the morning’s most important headlines for innovative Irish businesses.