Your crash course in... The rise and fall of Steorn, the energy firm that claimed to defy physics

The company, set up by the ‘Willy Wonka of energy’, reportedly raised €23m from investors.

HE WAS CALLED the ‘Willy Wonka of energy’ and claimed to have defied the laws of physics.

But after 16 years in operation, Shaun McCarthy confirmed in a recent Sunday Business Post interview that his controversial tech firm, Steorn, has shut its doors and will be liquidated.

The company claimed to have created an everlasting battery device that generated energy from nothing, as well as a mobile phone that never needed to be charged.

Even though its technology was lampooned by sceptics, Steorn managed to raise a reported €23 million from 400 private investors throughout the last decade.

With that in mind, let’s look at the rise and spectacular fall of Steorn, the company that tried to kill the battery.

‘Discovery’

Steorn set up shop in 2000, initially cashing in on the dot-com boom and working on a number of e-commerce platforms.

It was co-founded by engineer Shaun McCarthy, consultant Mike Daly, solicitor Francis Hackett and Shaun Menzies, of tech recruitment firm Zartis, who, incidentally, once travelled to the South Pole.

One of Steorn’s early projects was WorldofFruit.com, a much-hyped but ill-fated fruit trading site created by Fyffes.

A testament to the madness of the dot-com days, Fyffes’ company secretary at the time said it planned to float WorldofFruit on the Nasdaq market and projected $300 million in annual sales. Instead it lost nearly €5 million in its first year of trading when the bubble finally burst.

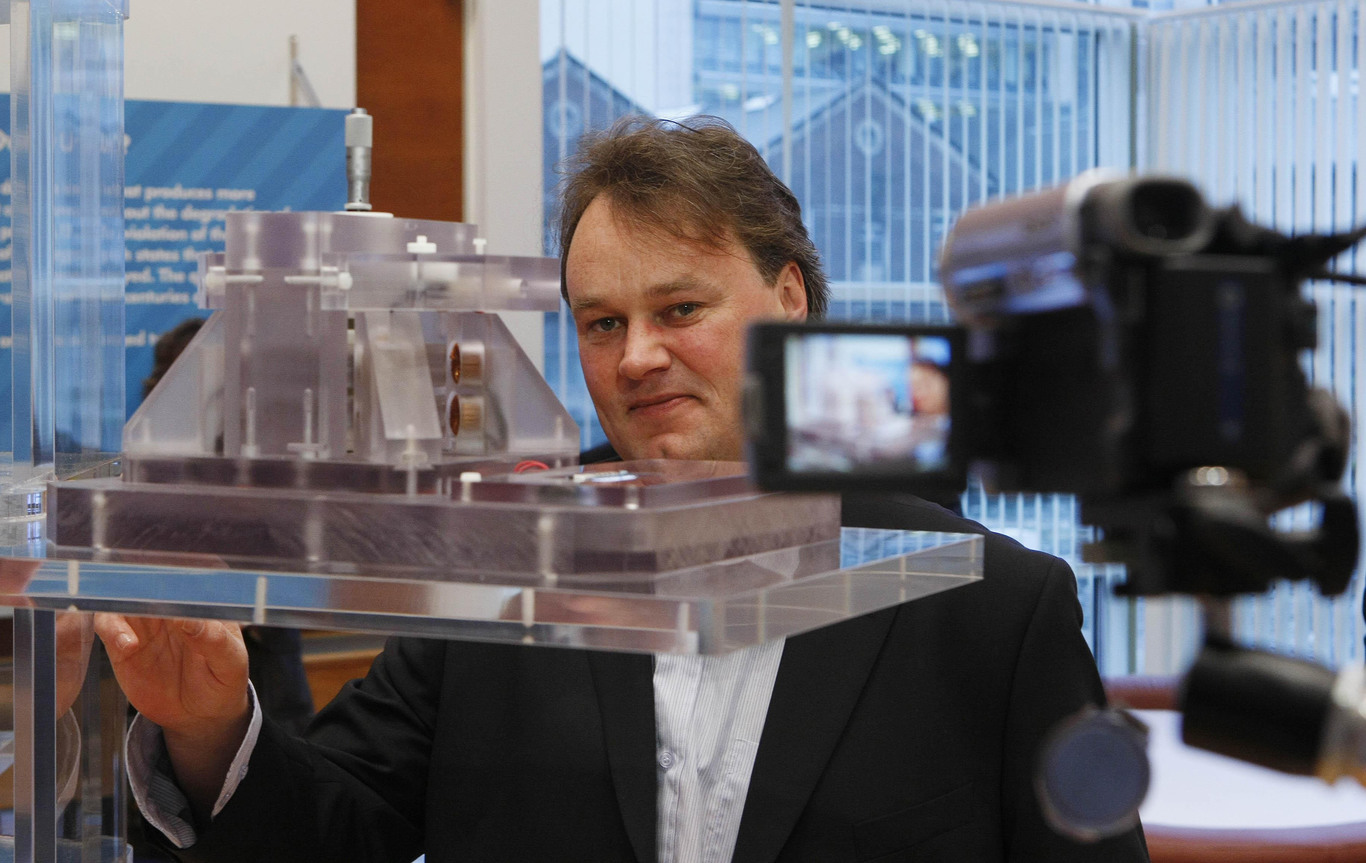

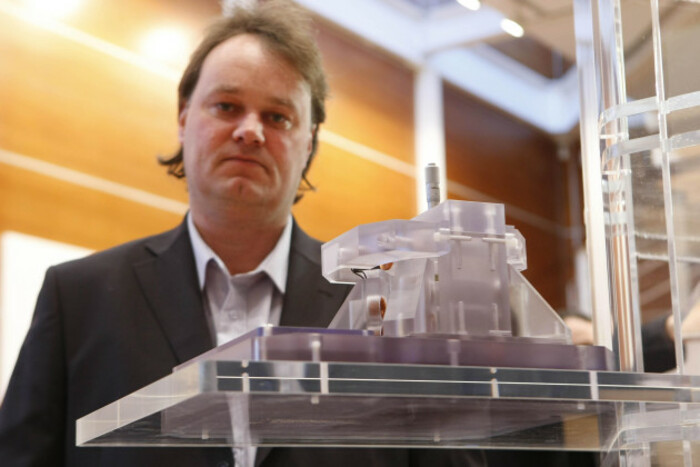

Steorn CEO Shaun McCarthy

Steorn CEO Shaun McCarthy

By 2006, Steorn had moved on from building internet platforms and shifted its focus onto the consumer electronics market. It said it was developing a device that would lengthen a mobile phone’s battery life.

The ‘eureka’ moment occurred three years earlier, according to an interview with McCarthy in The Guardian.

Steorn had been recruited by a bank to develop a system to prevent ‘skimming’, which is when an ATM machine is compromised to counterfeit cards and PIN codes.

The firm claimed to have invented a device made up of 16 mini CCTV cameras that could record the identity of fraudsters and catch them red-handed.

McCarthy told the newspaper: “We wanted the cameras to be independently powered, so we tried out small solar and ambient wind generators.

“We wanted to improve the performance of the wind generators – they were only about 60-70% efficient – so we experimented with certain generator configurations and then one day one of our guys came in and said: ‘We have a problem. We appear to be getting out more than we’re putting in’.”

That was the moment Steorn ‘discovered’ it could use magnets to basically create a perpetual motion machine – a mythical contraption that has fascinated inventors for decades and can supposedly defy the laws of thermodynamics, generating energy from nothing.

Just to put that into context, so-called ‘free energy’ would be a monumental discovery – it would eliminate the need to burn fossil fuels and make electricity cheaper and more accessible to people around the world.

The author of The Guardian article goes on to reveal that none of the eight electrical engineers and academics “with multiple PhDs” that McCarthy cited would go on the record to confirm they had validated the contraction. Nor would the company that had partnered with Steorn to manufacture a prototype.

The journalist was also promised a diagram explaining how exactly the system worked but it is never delivered because of concerns about intellectual property rights.

That Economist ad

In August 2006, McCarthy took out an infamous full-page ad in The Economist newspaper, which he said cost him £75,000 at the time, or about €88,000 by today’s exchange rate.

Emblazoned with a bold quote from George Bernard Shaw – “All great truths begin as blasphemies” – Steorn claimed to have created a technology that “produces free, clean and constant energy” and was “independently validated” by engineers and scientists – “always behind closed doors, always off the record”.

The ad invited scientists to test the battery device for themselves.

“We are seeking a jury of 12,” it said. “The most qualified and the most cynical.”

Michio Kaku was one of many physicists that dubbed Steorn’s device “a fraud” before the gadget was even tested.

“This company here does not use fancy superconductors or lasers, it’s just a simple magnet machine,” he told ABC News at the time.

In the end, a jury of 22 scientists – whittled down from 420 – took McCarthy’s challenge.

It announced in 2009 that it had wound down its investigation after finding no evidence that the Steorn contraption worked.

“Steorn’s attempts to demonstrate the claim have not shown the production of energy,” the group wrote in a statement.

Demo failures

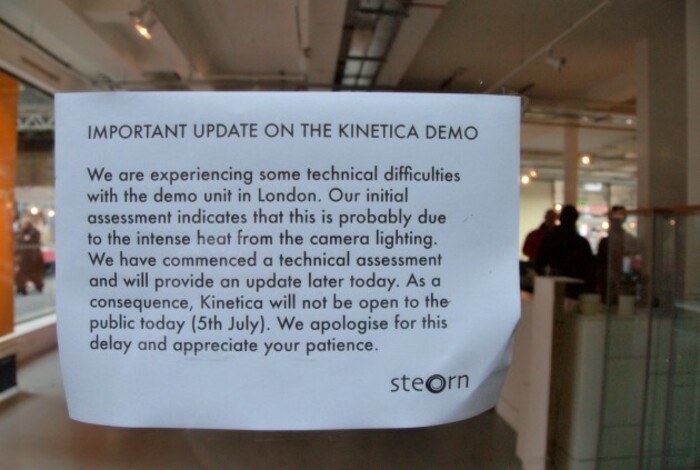

Perhaps the most high-profile misfire in Steorn’s history occurred in 2007. An early prototype of Orbo, its everlasting power device, was to be showcased at a demo, but it failed and Steorn cancelled the exhibit.

The malfunction was blamed on “excessive heat from the lighting in the main display area”.

“I screwed up,” McCarthy said in a Q&A afterwards, explaining that it had been functioning the days before. “It was a mistake entirely of my making … I have to take it on the chin.”

Steorn's notice in the Kinetica Museum

Steorn's notice in the Kinetica Museum

He promised to demo the device at a later date and hosted a series of exhibitions in the Waterways Centre in Dublin during 2009 and 2010.

McCarthy’s talk at the exhibition – billed under the daunting title ‘Orbo Electromagnetic Interaction COP > 1 – supposedly proved the existence of ‘overunity’, otherwise known as perpetual motion.

Using a oscilloscope device, which is used to measure the change of an electrical signal over time, he claimed that more energy was coming out of Orbo than was going in. Engineers were not convinced that McCarthy had proved anything.

Products

Undaunted, Steorn later launched two consumer products: the OCube, an everlasting USB charging device, and the O-Phone, a simple mobile phone that never needs to be charged.

The cube retailed at €1,200, while the phone cost €480. The company started taking orders in late 2015 for delivery in mid-2016.

In January of this year, The Irish Times visited Steorn’s East Wall headquarters to have a look at the OCube production line.

“This is, in many ways, a self-resolving controversy,” McCarthy told the newspaper. “Ultimately, the controversy that surrounds the fundamental claim of the technology is going to be resolved by consumers, not by us.”

In other words, Steorn relied on customers with cash to burn to take a punt on the product and prove that it worked.

Steorn's Ocube device

Steorn's Ocube device

McCarthy said he had disengaged with the scientific community and revealed that he wasn’t entirely sure how the free energy anomaly worked himself.

“We think that we’re converting time into energy … that’s the engineering principle,” he said.

“Do we understand the science? No, but we don’t understand gravity either.”

McCarthy also said that he never claimed to have created a perpetual motion machine. ”It’s not a machine,” he said. “(It’s) a battery that self-charges.”

The Sunday Business Post reported in July that the firm had withdrawn from sales of the two devices because many of the shipped devices didn’t work.

A letter seen by the newspaper said that Steorn was “a prospect that has been oversold to its investors … based on a naive optimism on time frames for tasks to be completed”.

What next?

Steorn has always been loss-making. Its most recent accounts show that it made a loss of €88,600 for the financial year ended 31 December 2014, pushing accumulated losses to more than €20.5 million.

The Sunday Business Post reported that it had tapped up investors this summer for more money, saying that it would be forced to wind-down the business otherwise.

However company filings to date show the last time shares for Steorn changed hands was in April 2013, when a stake was sold for €1.74 million to a group called The Steorn Orbo Trust.

The article also said that McCarthy had stepped down as chief executive, provisionally handing over the reins although he was due to stay on as operations officer.

Two weeks ago, the newspaper confirmed in an interview with McCarthy that Steorn had finally shut up shop and is to be liquidated. He said the company had no other choice because investment had dried up.

“It’s not that our existing investors didn’t show willingness to give more support,” he said, “but their capability to give support just kept diminishing.”

He said that would now earn a living through online poker and described himself as “unemployable” because of his association with Steorn.

“The general perception is (that I’m either) a conman or an idiot because clearly the tech can’t work,” he said.

That said, he didn’t write off Steorn’s technology completely and insisted that it still had potential.

“Whoever the liquidator turns out to be, hopefully will get a bidding war for it,” he said.