Your crash course in... the murky and unregulated world of shadow banking

Here are the key points you need to know about the shady system that keeps the financial world ticking over.

IT’S A TERM you may have heard of before due to its role in the worldwide financial crash in 2008, but ‘shadow banking’ isn’t everyone’s go-to Mastermind topic.

The term crept back into the headlines today after the Irish Times reported that Aine Hollingsworth, a principal officer with the Revenue Commissioners, had concerns about how the law-firm Matheson was involved with shadow banking.

Shadow banking is quite a big deal in Ireland. A report from Financial Stability Board (FSB), the regulatory task force for the G20, earlier this year showed Ireland has the highest level of shadow banking assets in the world as a percentage of GDP.

In fact, with €2.3 trillion of assets, Ireland is the biggest hub for non-bank finance after the US and UK.

Not ones to shy away from complex matters, this week we have decided to delve into the world of shadow banking to explain what’s going on.

The basics of shadow banking

Shadow banking is a system of financial entities, all of which have the same functions as traditional banks, and is for the most part unregulated.

Unlike a lot of traditional banks, those in the shadow banking sector don’t have any access to central bank funding or something like a safety net in place to protect the company if disaster struck.

The system is made up of many different entities such as hedge funds, special purpose vehicles (SPVs), money-market funds and other types of financial institutions.

Although they sound quite ominous, the shadow bank system is essential because it props up its traditional counterparts by providing funding to the mainstream banks that is needed to provide different types of loans.

How does it differ to traditional banking?

Like traditional banks, shadow banks offer loans, however, these loans are normally offered with less interest attached.

Another difference between the two lies in what they do with the loans. At a shadow bank, the loans are not kept on the books instead, they are bundled up and turned into bonds.

For example, Kevin the shadow banker may have an expertise in home loans and may lend to 100 people at an interest rate of 9%. Kevin would group these loans together and sell them as a bond to an investor, who would then be paid interest of maybe 2% on their investment. This creates a flow of cash back to the shadow bank to loan out.

Another difference between the two is that shadow banks don’t fall under the regulations applicable to traditional banks.

One such example is capital adequacy, which means that banks need a certain amount of money on their balance sheet relevant to the loans it has taken on. This is a safety net to ensure the bank has enough cash in case everything hits the fan.

US Nobel Prize of Economy winner Paul Krugman

US Nobel Prize of Economy winner Paul Krugman

Why should you care?

Well, according to Paul Krugman, who tends to know a thing or two about economics, shadow banks were mainly responsible for what brought about the global recession.

Just before the economic crash, shadow banking became such a key facet of the economy and began to command more than half of the lending market because traditional banks couldn’t keep up with the loan demand and often struggled to match the rates offered by their unregulated counterparts.

After the financial crisis, a lot of the banks that took risks which led to the crash were given a slap on the wrist and reined in, but since shadow banking is largely unregulated, the industry didn’t get a telling off for its role in the recession.

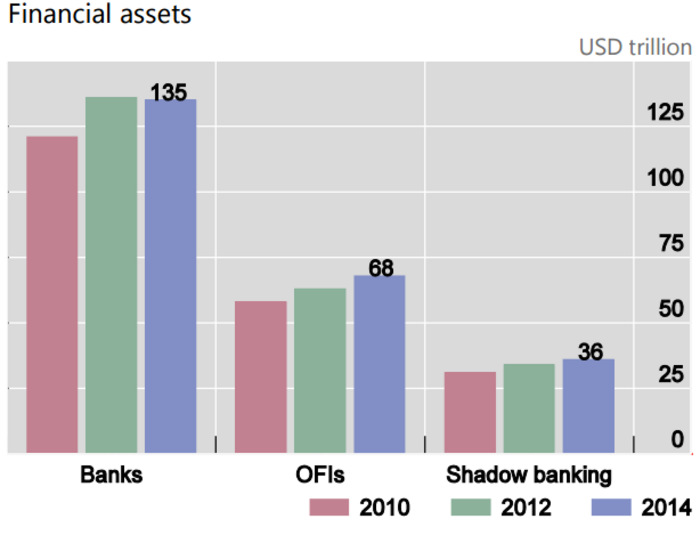

Shadow banking still accounts for a large section of the total financial system, according to the FSB, and is still largely unregulated.

Regulators worldwide have warned that the shadow banking industry could cause an even more dangerous recession as the industry has no failsafes in place like traditional banks, meaning it could create a domino effect if they started to collapse.

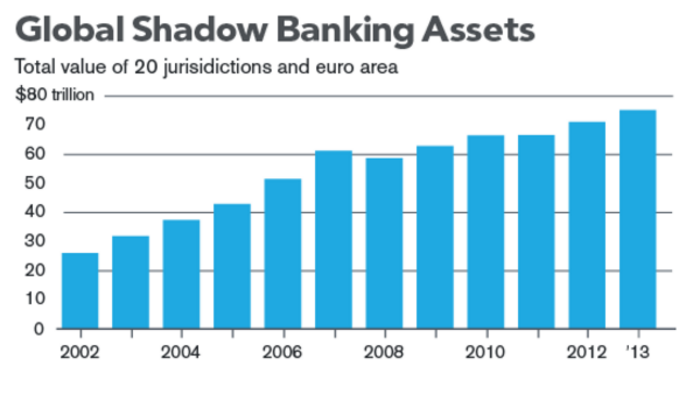

In 2014, the sector actually grew by $5 trillion to a value of $80 trillion. The FSB’s shadow banking report also showed that three-quarters of the world’s economies displayed an increase in shadow banking activity and in China alone the practice increased by 30%.

Where is this going on?

It’s going on in most parts of the world that were hammered by the global recession, which is to say pretty much everywhere. Shadow banks have essentially picked up the pieces from their traditional counterparts after they were hit by losses.

However, it is not all good news for shadow banking because investors are starting to catch on to how dangerous it can be.

Some anxiety was caused in Asia earlier this week when documents filed to the Hong Kong stock exchange showed that the Postal Savings Bank of China has $143 billion (€129 billion) of interbank investments in SPVs, which are financial institutions used to stop certain assets from appearing on a company’s balance sheet .

The revelation that the Chinese lender has investments in SPVs could put a spanner in its plans to raise $8 billion dollars through an initial public offering and make investors think twice about the company as a good investment.

Why don’t governments crackdown on it?

There’s a very simple answer: the shadow banking system keeps everything ticking over, especially in developing countries.

Countries like China need shadow banking because certain sectors are starved of funding due to the government discouraging traditional banks from lending to specific industries.

The US has made inroads into getting a grip on the shadow banking system by forcing banks to declare SPVs on balance sheets.

A similar move was made closer to home by the Central Bank after the organisation flagged last year that SPVs are a threat to international financial stability.

Now Irish SPVs are obliged to alert the Central Bank of their presence even if their activities do not affect regulated areas.