Your crash course in... Why foreign airlines are queuing to set up operations in Ireland

Sweden’s SAS airline is the latest carrier to apply for an Irish air operators licence.

SWEDISH AIRLINE SAS announced this week that it has applied for an Irish air operator certificate, or AOC.

That means it will set up a management team and register planes here.

Those Irish-registered jets will be based in London and Spain for use on “a small number of departures to complement existing services” that SAS operates, according to a statement on the airline’s website.

Of course, SAS won’t be the first foreign airline to apply for an AOC in Ireland – its Scandi rival, Norwegian Air, was granted a certificate for its subsidiary in Dublin three years ago.

SAS is following Norwegian’s flight path so it can “reduce the cost differential to newly established competitors” - a clear message that it wants to up its game against its ‘low-cost’ competitor.

So, how exactly would having an Irish licence help the overseas carrier drive down costs? Let’s look at why foreign airlines are queuing to set up offices in Ireland.

A SAS Boeing 737

A SAS Boeing 737

What is an AOC?

A company that operates commercial flights is required by law to hold a valid AOC from any national aviation authority.

In Ireland’s case, the IAA is responsible for registering civil aircraft and approving AOCs.

In a nutshell, the certificate means that the airline operates under the regulations in the chosen jurisdiction. The company is granted the protection of that country’s aviation agreements.

For SAS, having an Irish AOC means it plays by labour laws here, which are comparatively favourable to employers than the much stricter rules in Sweden.

SAS has made no secret about this. It said it will hire staff locally. In a statement to several news outlets, spokesman Fredrik Hendriksson said that the cost advantage of an Irish AOC would come from having lower social security expenses and taxes.

It’s interesting that one of the main objections to granting Norwegian’s Irish subsidiary access to the US market was over fears that Ireland was being used to skirt labour laws.

Bilateral agreements

A key selling point of an Irish AOC is that it grants airlines access to the clatter of bilateral agreements Ireland has struck up with other regions around the globe.

Many of the treaties Ireland signed with other countries date back to the days when Shannon Airport was a compulsory refueling stopover for airlines operating long-haul routes.

A historical accident caused by our barrage of bilateral deals is that Ireland is more favourable to airlines in terms of tax law, accountancy rules and on a bureaucratic level.

For example, Ireland offers a tax depreciation on aircraft of 12.5% per year over an eight-year period. That can be used to reduce the amount of taxable income reported by a business.

A private jet refueling at Shannon

A private jet refueling at Shannon

Our national bilateral agreements became less important in recent years, especially after the EU-US open skies agreement was signed, which made it easier for carriers to fly between Europe and the US.

They’re becoming an attractive asset again with Britain set to exit the EU. There’s a good chance you’ll hear more about Ireland’s AOC as airlines move UK-registered jets to maintain access to the EU travel zone.

History

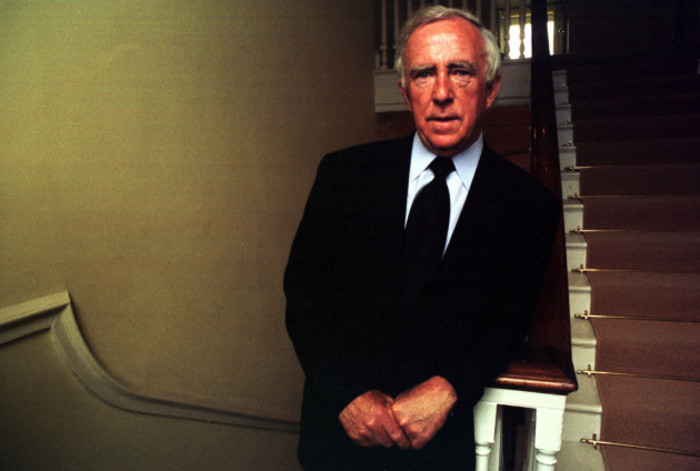

The noble story of Ireland’s great aviators – like leasing legend Tony Ryan, who went on to co-found Ryanair, one of the country’s most successful companies – certainly helps Ireland live up to its reputation as a ‘centre of excellence’ in the air travel business.

But the story alone isn’t exactly a deal breaker when it comes to making boardroom decisions. It’s more significant that our long history of flight means we know how to ‘talk aviation’.

Tony Ryan

Tony Ryan

Regulation agencies here are more familiar with how the industry works because it is so big: aviation contributes an estimated €4 billion to our economy, according to the IAA, and roughly half of the world’s aircraft are owned by Irish-based leasing companies.

We have developed a culture of aviation and we understand the requirements of an business in the industry.

Anywhere there’s a meeting of airline bigwigs putting together a business plan, there’s a good chance an Irish person is sitting somewhere at the boardroom table.