'Dublin is not a low-rise city - it's even lower than that'

Taller buildings and increased density would improve quality of life in the capital.

IRELAND’S GROWING POPULATION raises the big question of where we can call home.

Unfortunately, housing availability and affordability is damaging the quality of life of many people and undermining Ireland’s competitiveness. We urgently need a sensible approach to urban building height limits.

Getting this right will allow us to address the problems of urban sprawl, housing and commercial space shortages and improved densification.

Our cities will also be better positioned to attract a new wave of investment and jobs, especially in the post-Brexit era.

Dublin is not a low-rise city

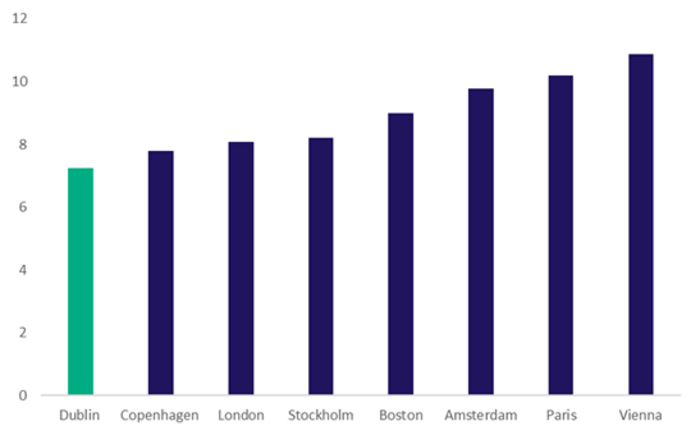

A common argument against tall buildings is that Dublin is a low-rise city. This lacks a common definition of ‘low rise’. Dublin is, in fact, far lower in height than other European cities that anti-height proponents put forward to justify the status quo.

Average building heights in Dublin are lower than other cities across Europe, including comparably sized cities such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Stockholm.

Calculations based on Copernicus Urban Atlas

Calculations based on Copernicus Urban Atlas

Georgian proportions have defined the Dublin skyline for the last 250 years, but standards established then should not be the sole determinant for the ambition or natural evolution of the city for the next 250 years.

This position contributes to urban sprawl, prioritising the character of a few areas over developing the green belt within and outside the city.

Dublin is not unique internationally in its dominance of Georgian house proportions or character. Comparative Georgian cities, such as London or Boston, have higher average building heights than Dublin.

Closer to home, Limerick has earmarked its Georgian quarter to spearhead its ambitious regeneration initiative for the city.

Time to rethink

Height must be a core component of our urban density ambition. It must be allowed in a manageable and sensible way.

In developing policy on building heights, attention should be paid to international best practice in urban design and regeneration and acknowledge that clusters of well-designed taller buildings can provide housing and make a beneficial contribution to their surrounding streetscape and skyline.

The focus should be on actively promoting good design within the context of place-making.

Public discourse too often points to past failures when it comes to high density, most notably developments such as the Ballymun flats.

This is misused as justification for not pursuing new projects that can accommodate a growing population affordably, safely and sustainably.

Instead, society requires us to put the lessons learnt to constructive use. Evidence from cities across the world should be used to inform stakeholders on height in the context of good planning policy.

The approach taken by local authorities is inconsistent and incoherent. Developments in Cork city and Sandyford are taller than projects initiated in the Dublin City Council area.

Planned government guidelines on apartment heights are a welcome start, but more can be done. Dublin’s four local authorities, for example, should come together to develop a specific tall buildings strategy, earmarking locations for such development.

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat considers ‘a building of 14 or more storeys – or more than 50m in height – could typically be used as a threshold for a “tall building”’.

This is double the permissible height for residential developments in central Dublin.

There is a lack of ambition and an unwillingness to deal with density issues in Dublin city.

Of the 14 specific areas identified for mid-rise (up to 50m) and taller (above 50m) buildings, we already have examples of failed planning applications in these areas despite their designation in policy.

Georgian Dublin

Georgian Dublin

People must be able to live and work in a city

We must balance the requirements of commercial and housing developments within our cities. People should be able to choose to live close to where they work.

This requires local authorities not to implement policies that, intended or not, prioritise one over the other.

Dublin City Council has a lower maximum height requirement for residential buildings than for commercial premises in the inner city. This policy left unchecked will only encourage more sprawl.

Not everyone wants to live in an apartment, that’s true. But an increasing number of people do. This is often overlooked in public commentary.

The issue with taller buildings and apartments in general is that policymakers appear to have let personal biases override the sustainable development of Irish cities. This must change, and it must change now.

Height and density needs to be planned to improve quality of life within our cities. This will allow Ireland to become more competitive, resilient and inclusive.

We must recognise that urban planning necessitates building communities, not just housing. All of this impacts a city’s ability to attract or retain people.

We must seize on the opportunity that the National Planning Framework affords to better connect quality of life and place.

Aidan Sweeney is a senior policy executive at Ibec.