How iPads sparked a week from hell for the company behind Ireland's biggest moneylender

Provident Financial is being investigated by the UK’s financial watchdog.

IT HAS BEEN a disastrous week for Provident Financial, the British moneylender that offers door-to-door, high-interest loans to people with poor credit ratings.

The company, parent of Irish outfit Provident Personal Credit, announced yesterday that it expects to report a full-year loss of between £80 million and £120 million – its second profit warning in three months.

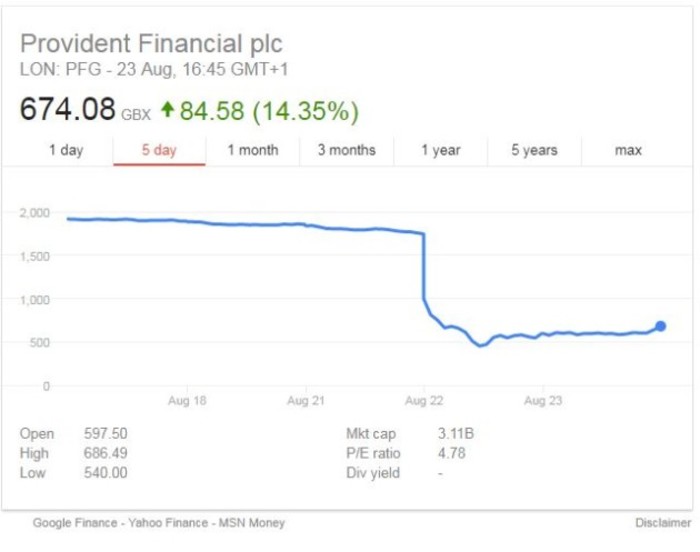

The news sent Provident Financial’s share price spiraling, dropping as much as 76% and wiping about £2 billion off its London Stock Exchange valuation.

To top it all off, chief executive Peter Crook stepped down after 10 years in the role and it emerged that Provident is being investigated by the UK’s financial watchdog.

This is what you need to know about Provident’s week from hell.

High-cost loans

Based in Yorkshire, Provident Financial is a FTSE 100 company that specialises in ‘subprime lending’ – financial jargon for loans given to people who may ordinarily have difficulty in obtaining – and repaying – them.

The company grew rapidly in the years after the economic downturn, offering credit to borrowers who couldn’t secure finance from banks that were scarred by the crash. Since they’re more risky, subprime loans typically carry high interest rates.

Click here to view a larger version.

Provident’s Irish subsidiary, Waterford-based Provident Personal Credit, charges headline interest rates of 60% per year – so a loan of €600 paid back over 26 weeks would require €780 to repay within the term.

In 2014 the company was fined €105,000 by the Central Bank for offering new loans to customers to allow them to repay existing loans with the firm.

In the UK, Provident is known for its ‘doorstep’ sales technique. Agents travel door-to-door, selling loans and acting as a sort of debt collection agency when borrowers fail to make a repayment.

It also runs Vanquis Bank, which provides Visa-branded credit cards to people with limited or poor credit history.

FCA probe

Vanquis Bank is at the centre of the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) probe into Provident.

According to the company, the financial watchdog is investigating Vanquis’ ‘repayment option plan’, or ROP, which generates revenues of about £70 million each year.

“The FCA indicated that it has concerns about the ROP product and is investigating the period from 1 April 2014 to 19 April 2016,” the company said in a statement, without explaining the problem.

Provident Financial's ex-CEO Peter Crook

Provident Financial's ex-CEO Peter Crook

Vanquis Bank was ordered to suspend all new sales of the payment-protection product in April of last year and was ordered to contact all customers.

It also made an agreement with the Bank of England’s regulatory body not to pay dividends or “enter into certain transactions” with other parts of the Provident group without consent.

Backfire

Provident Financial has another massive problem on its hands besides the knocked share price, CEO vacancy, FCA probe and profit warning.

Earlier this year, the company rolled out a major overhaul of its business model – but the move has backfired miserably.

In a bid to embrace technology and cut costs, Provident ditched its team of 4,500 self-employed, door-to-door salespeople and replaced them with 2,500 full-time ‘customer experience managers’.

The workers were armed with iPads fitted with analytical software that was supposed to help them use their time fore efficiently. Instead, there was a major drop off in debt collection.

According to the Guardian newspaper, Provident’s debt collection rates fell from 90% last year to just 57%. It’s not clear yet why the iPad-wielding managers have performed so badly.

“What’s questionable is why this iPad revolution needed to happen at all,” Lionel Laurent wrote in a Bloomberg column.

Citing data provided by the business intelligence firm, Laurent noted that for the last five years Provident boasted a healthy return on common equity – a measurement of a firm’s ability to create profits from shareholders’ investment.

The company also enjoyed a cost-to-income ratio that was “low enough to make even Llyods Banking Group blush”, Laurent said.

“Yet the bank still presented its IT overhaul in April as a way to cut high management costs’ and ramp up scrutiny and transparency. An increasingly twitchy regulator probably also contributed,” he said.

“The new model would put ‘clear blue water’ between Provident and the rest of the market, the firm said. It has – just not in the way the firm intended.”