'There's no regard for people': Why Cork locals are fighting plans to harvest seaweed

Tralee-based company BioAtlantis wants to harvest Bantry’s kelp for bioengineering purposes.

A GROUP OF residents in Co Cork is protesting the government’s decision to grant a licence for the mass mechanical harvesting of kelp seaweed in the local bay to a Kerry company.

The ‘Protect Our Native Kelp Forest’ campaign in Bantry is protesting the 2014 granting of a 10-year experimental harvesting licence to Tralee-based bioengineering company BioAtlantis.

The protest group claims that the statutory public notice required by the government regarding what was being planned for Bantry’s offshore kelp (an advert in a local paper, and a notice held under lock and key at the local garda station) was insufficient.

BioAtlantis strenuously asserts that it satisfied every condition demanded by the State and that it would have gone even further in its bid for compliance if asked to do so by the Government.

“There has been a lot of misinformation in relation to this,” the company’s CEO John O’Sullivan says.

The Bantry residents, meanwhile, also say that BioAtlantis’ plans will irreparably damage the local sea environment – both in the case of the kelp itself and also the local marine life which they say is dependent upon the seaweed’s presence. BioAtlantis denies this.

The group has complained that the licence, which was granted in 2014 by the then-Minister for the Environment Phil Hogan, and first applied for in 2009 to the Department of Agriculture, was given without an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) being carried out.

The Department of Housing, which currently has responsibility for foreshore (ie the area between the high and low water marks of a seashore) activities says that under European law, no such assessment was required, nor was it deemed necessary by the government of the time.

Harvesting of sections of the region’s kelp forest is expected to commence in the near future.

“We had no idea any licence had been granted until February when it showed up on RTÉ,” local woman (and group member) Deirdre Fitzgerald told TheJournal.ie (the programme in question was an edition of Eco Eye on the State broadcaster).

Fitzgerald claims that a “litany of questionable things” regarding the granting of the licence are behind the residents’ protest – a campaign that has seen a petition calling for the licence to be revoked garner nearly 7,000 signatures online.

Nor is the Bantry group satisfied with the levels of public consultation. “The consultation with the local community consisted of a tiny ad in a local paper that did not specify what was planned,” says Fitzgerald.

“No regard has been shown for the people who rely on tourism and marine activities such as fishing in the bay to make a living,” she adds.

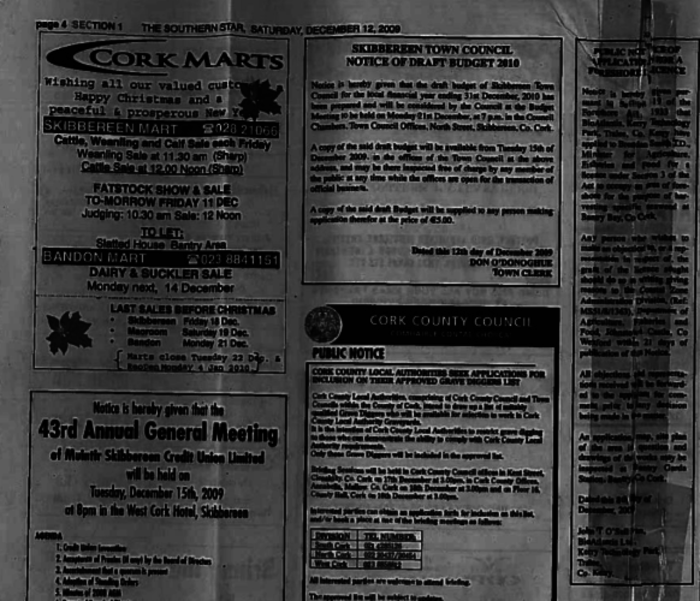

Advert (on right) in the Southern Star regarding the application for a licence by BioAtlantis, December 2009

Advert (on right) in the Southern Star regarding the application for a licence by BioAtlantis, December 2009

Click here to view a larger image

BioAtlantis, for its part, says that all established protocols have been followed, both in applying for the licence and in the future harvesting that has been planned.

“Our issue is not with the company. They have done all that they were asked. It is with the government letting this happen without letting the locals know,” says Fitzgerald.

“I mean you’re talking about one of the biggest mechanical harvesting operations in the history of the State.”

Expert group

For many hundreds of years seaweed has been harvested off Ireland’s shores by hand. However, mechanisation of the process has in recent times become more prevalent in other European countries such as Norway and France.

The use of seaweed and kelp for research, treatments, natural beauty products, and food is big business in Ireland and Europe at present. In 2014, the worldwide seaweed industry was estimated to be worth €5.25 billion.

A 2015 report by Irish seafood development agency Bord Iascaigh Mhara (BIM) suggested that demand in Europe for sea vegetables is growing by up to 10% each year.

While seaweed has been farmed by hand for hundreds of years in Ireland, and the use of the plant in both nutrition supplements and beauty products is well-documented, BioAtlantis is not a cosmetics company.

The 13-year-old Kerry business plans to use the harvested seaweed as a means to develop alternatives to the use of antibiotics in the feed of farmed animals.

“We would completely disagree that there was not proper consultation,” O’Sullivan told TheJournal.ie regarding the granting of the 10-year harvesting licence to his company.

“The action taken by BioAtlantis and approved by the government in the form of a trial licence is exactly as recommended by an expert group.

“Eight different bodies with specialists in the area assessed the application. The Marine Licence Vetting Committee (MLVC) concluded that subject to compliance with specific conditions harvesting was unlikely to have a significant negative impact on the marine environment.

“If there were other requirements in relation to consultation then BioAtlantis would have complied with these also.”

O’Sullivan, likewise, claims that “the decision to grant a licence obtained cross-party political support”, given it was originally approved by the Green Party’s John Gormley in 2011, before being officially granted by then Labour Minister for the Environment Alan Kelly in 2014.

Currently, the Department of Housing (and its newest Minister Eoghan Murphy) has jurisdiction over the issue.

“Normal public consultation procedures were followed with the application,” a spokesperson for the Department told TheJournal.ie.

“No submissions were received from members of the public during the consultation period,” they added.

The local protest group counters this fact by saying Bantry Garda Station kept the notice in a filing cabinet to be produced only when the public asked to see it, and the scale of the licence was not made clear.

TheJournal.ie contacted Bantry gardaí to confirm that this is indeed the case: “That is the policy, and is so for all such applications, not just sea licences,” a spokesperson said.

“You come into the station and ask to view it, we produce it and you can view it, but it cannot be copied and cannot be taken away.”

When asked how the public can know about something if it is not visible, the spokesperson replied: “I don’t think the facilities are here to put it on public display.”

An Environmental Impact Assessment meanwhile was, according to the Department, not required as the “proposed project was not within a Natura 2000 site (Natura 2000 is a European network of important ecological sites)”.

A spokesman said that the “sustainability” of any mechanical harvesting would be subject “to a strict monitoring programme”.

“The licensed area is split into five distinct harvesting zones and not all of the seaweed in the bay will be harvested,” he said.

Opposition

Much of the criticism levelled at the granting of the licence has been at the level of public consultation required by the relevant state bodies.

In a letter to the Department of Housing in June, Cork coastal marine environmental expert Seán Lynch described a situation in which a licence of the sort granted to BioAtlantis without adequate public consultation as being “entirely irresponsible”.

“Marine spatial plans should aim for sustainable and efficient use of marine space by maximising multiple uses and where necessary for the management of conflicts or to highlight specific opportunities for potential investors the zoning for preferred uses,” Lynch said.

“Meaningful and early consultation with all stakeholders including the general public, is essential.

“In my honest opinion such a lack of foresight severely undermines the Department’s ability for good governance.”

BioAtlantis’ experience in Bantry, meanwhile, is not the only strained situation the company has found itself in with locals regarding the mechanical harvest of an area’s seaweed.

In 2015, the Mayo News reported that locals in Clew Bay in the western county had set up their own seaweed association, a move prompted by BioAtlantis seeking a 10-year exclusive licence to harvest the coastline’s seaweed.

The situation prompted local Fine Gael TD Michael Ring (now Minister for Community and Rural Affairs) to “outline his dissatisfaction… about the proposals” to then Housing Minister Paudie Coffey.

Back in Bantry, public opposition to the granting of the harvest licence appears to be growing.

“People have the right to sign petitions but it would be interesting to know whether they are aware of the facts,” says O’Sullivan.

“Kelp is proven to regenerate between three and six years post-harvest,” he added. (A key claim of the Bantry protest group is that mechanically cutting the kelp 25 centimetres from the root “will effectively kill the plant”.)

“The description of kelp as a forest is inaccurate as it gives the impression of something old and covered with trees. This is not true.

“Kelp is a type of algae or seaweed, it is not a type of tree. It grows quickly unlike a tree and has a short generation time. Kelp in Bantry Bay is only three-to-five years old.”

And as for a commencement date for harvesting?

“There is no fixed commencement date; we are not ready to start yet.”

Written by Cianan Brennan and posted on TheJournal.ie