For these Irish companies, space is no longer the final frontier

The sector is predicted to double exports within four years amid a resurgence in space technology.

AFTER DECADES ON the periphery when the lustre of the lunar expeditions faded, the space industry has lately been enjoying a renaissance.

Spurred by the appeal of entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and his SpaceX, a number of high-profile missions from the European Space Agency (ESA) have also helped catapult the industry back into the public’s imagination across the continent.

Once dominated by the Cold War superpowers, countries such as Ireland have been given the opportunity to emerge as small but important cogs in the captivating – and potentially lucrative – sector.

The Irish government expects the number of people employed in the space industry in the Republic to breach the 1,000 mark in the next four years, and with backing from the ESA it has launched a ‘space business incubator’ that will help grow 25 space startups on these shores.

The number of firms active in the sector in Ireland is expected to reach 80, while total revenues at the companies is forecast to nearly double from €76 million in 2015 to €135 million by 2020.

Danny Gleeson, the chair of the Irish Space Industry Group, says high-profile success stories like PayPal and Telsa founder Musk’s privately funded SpaceX have helped put space back on the agenda.

“Achieving space missions and objectives at low cost is in everyone’s mind and SpaceX is driving that with its low-cost launcher. The resurgence of manned space flight and the work on the International Space Station with humans on board is now normal,” he tells Fora.

“The excitement has also comes from the pressing need for data on demand and global communications. How do you put those things in place?

“You can use very expensive €500 million telecommunications satellites that are single-point failures or, counter to that, we can now put up lots of small cheap satellites to achieve the same thing.”

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk with the Dragon V2 vessel

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk with the Dragon V2 vessel

The significant reduction in costs for the devices and materials used in space travel is one of the key factors behind momentum in the industry picking up.

While government funding in many cases has plunged – Nasa’s share of the US federal budget dropped from 4.4% in 1966 to 0.5% in 2014 – private-industry players have become increasingly active in the sector.

Nowadays, even a startup can feasibly launch a satellite into space.

‘People stopped believing’

Barry Lunn, the CEO of Limerick-based satellite communications and space radar developer Arralis, also credits a lot of the hype around the space industry globally to the likes of SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin.

“When I was growing up, we all thought we were going to land on the moon and that died off for a while and people stopped believing. That’s why it has been really refreshing with the likes of big companies re-imagining space.

“In the US, the amount of startups in the space sector is remarkable. I met three startups over in America that are launching their own satellites. People would have laughed at you five years ago if you said that. You couldn’t have done it for the price point you can do it today.”

Arralis CEO Barry Lunn (second from the right)

Arralis CEO Barry Lunn (second from the right)

Much of the momentum behind Irish companies emerging in the space sector has been fueled by funding from the ESA, which has an annual budget of roughly €5 billion.

Ireland was one of the earliest members of the Paris-based agency and with a contribution of just €17 million to the organisation last year, the returns from the space industry here make continued state support a no-brainer, according to Gleeson.

“Ireland gets back between two and three times what it invests. During the downturn, one of the few budgets that was increased was the contribution to ESA because it was giving back more than was put in,” he says.

“The goal of the industry is to work with the government to develop policy to grow the space sector through investing in the ESA and using its programmes to develop technologies that we can then grow the export market for.

“It’s important that the government grows the ESA investment because it’s evidence based. It’s demonstrated that you get back more than you can put in and you can then spend that return on health and education and so on.”

In addition to his role with the Irish Space Industry Group, Gleeson is also the space business development manager for the multinational Curtiss-Wright, which has a base in Dublin.

The local branch has been involved in developing data-acquisition systems that control the sensors on experimental space vehicles being developed by the ESA. It also provides equipment for SpaceX’s Dragon re-entry vehicle and Falcon 9 launcher and recently signed a deal to develop data-collection gear for US company RocketLab.

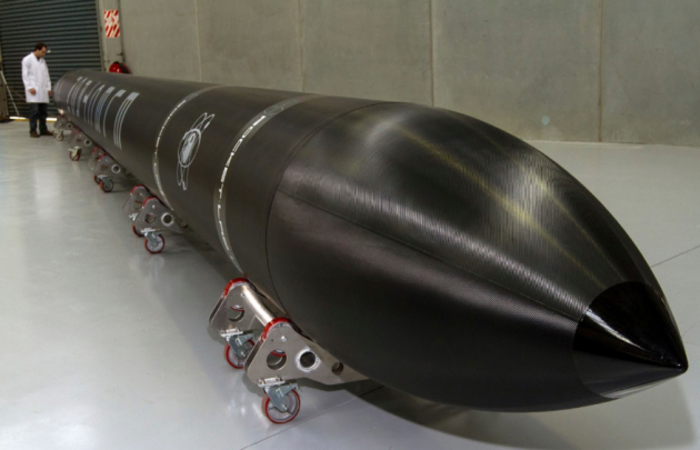

A space rocket developed by RocketLab

A space rocket developed by RocketLab

Adapting the technology

However the future of Irish companies in the space sector will depend on how well they can find commercial applications for the technology from ESA-funded projects, according to Tony McDonald, who oversees the sector for Enterprise Ireland.

“The ESA have companies to develop technology and qualify it for space, but the real issue is how companies can commercialise that tech in the space market or maybe even transfer it into a non-space market.

“Companies developing technology for space are finding that there is a lot of spin-out potential into non-space related activities.

“Some companies can make money in space where you have a higher volume of activity, like satellite communications and launchers. We’re also seeing an increasing number of companies in Ireland that are taking their technology into other sectors like aerospace, medical and automotive.”

One such Irish company that has developed tech for use in manned space flights which can also be sold into more mainstream industries is Cork-based Radisens Diagnostics.

The company has been awarded two contracts by the ESA worth €1 million each to develop a device that can test astronauts’ blood in a zero-gravity environment and is adaptable to healthcare sectors.

Chief executive Jerry O’Brien says the machine can test for chronic diseases with a single prick of blood and give results within minutes.

“There is a big requirement for testing blood in astronauts, not only for monitoring their health but in planning long-term missions.

“Up until now, in the space station they have had to store large vials of blood and transport them down to earth for testing later on, for which there is storage and time lag implications.

“In our technology, the blood is contained in a cartridge that spins in the instrument, which means it can work in zero gravity.”

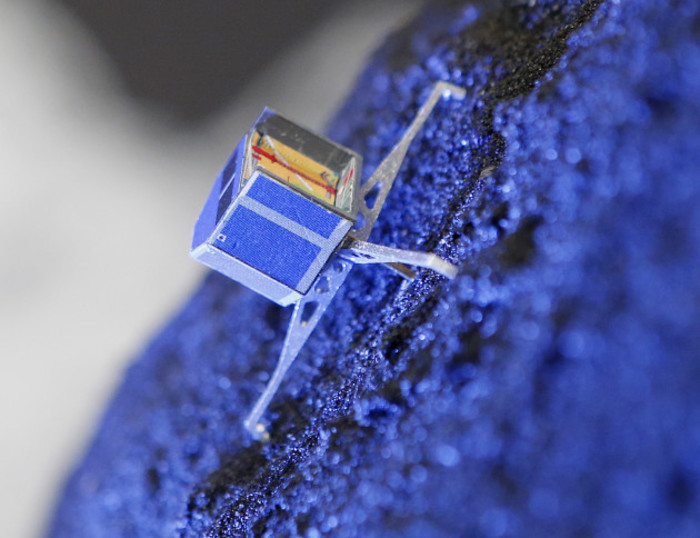

A model of the ESA's Rosetta lander Philae

A model of the ESA's Rosetta lander Philae

O’Brien says all research projects the company gets involved in with the ESA need to pay dividends for both parties and it’s very important that any tech developed is adaptable to sectors beyond the space industry to maximise its commercial potential.

Arralis has also benefited from the agency’s funding over two different contracts, and it is currently looking at a third.

Lunn says that work has been like a stamp of approval for the company, giving it a pedigree when looking to seal other commercial deals.

“You will not develop technology on an ESA contract and come out the other end with a dud. It’s not a grant, it’s procurement.

“You have to deliver what you said you would deliver and there is no room for error. So that means you are coming into the marketplace with a product and that product comes with a reference from a space agency.

“We’re now working with six of the top 10 aerospace companies in the world. There is no way we would have gotten there without the ESA stamp and the financial support.”