Your crash course in... Ireland's mortgage-rate problem

These are the key points you need to know about the latest attempts to force banks into action.

THE IRISH PUBLIC got a glimpse of the new political reality when a bill to cap mortgage rates that the finance minister branded as potentially unconstitutional was waved through the Dáil yesterday.

The issue of high rates being paid by Irish borrowers has been on the agenda for years and any move to limit lenders’ charges is likely to go down well with voters.

But there are still a few hurdles to be crossed before the bill makes it into law – not to mention questions over what will happen next if that does take place.

Wait, what’s the problem again?

Nobody likes being ripped off and the widespread conception is that’s exactly what’s happening to Irish homeowners.

While variable mortgage rates in the Republic have been slowly sliding over the past year as the banks start delivering profits again, the average rate still stands above 3.6%.

That compares to roughly 2% for new business across Europe, where lenders have been enjoying rock-bottom funding costs.

The issue affects an estimated 300,000 customers paying above the odds for their homes.

What’s being done?

Finance Minister Michael Noonan went for the tough-talk approach last year, when he warned the country’s six main lenders they could be slugged with penalties if they didn’t drop their rates.

And the banks responded – although that may have much more to do with their significantly improved bottom lines and a bit of competition in the Irish market rather than anything the former schoolteacher had to say.

AIB plans to drop its variable rates to 3.4% in July and the state-owned lender is tipped to go further, particularly with a cut-price rival in Frank Money planning to offer rates as low as 2.8% if it gets cleared to operate by the Central Bank.

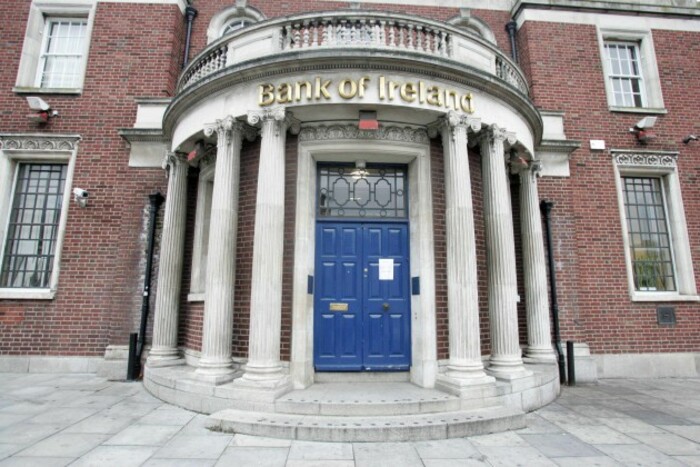

But others have been much tardier in passing on any reductions. The Bank of Ireland, which delivered an underlying pre-tax profit of €1.2 billion last year, is now as much as one percentage point more expensive than its pillar-bank rival.

It has been focussing instead on locking new borrowers into fixed rates rather than offering savings to its existing customers.

Overall, the cuts have only been enough to bring down the average variable mortgage rate in Ireland around half a percentage point.

Enter Fianna Fáil, which has been positioning itself as the chief defender of homeowners who have found themselves bolstering the banks.

It tabled a bill on Tuesday that would give the Central Bank powers to cap variable mortgage rates with the party’s stated aim to essentially force rates down.

That measure was duly waved through to the committee stage with the support of Sinn Féin and Labour, with Fine Gael opting to not to press its own amendments nor vote against the bill.

So does that mean cheaper mortgages then?

While forcing banks to lower their rates seems like a good idea and will probably go down well with mortgagors, whether it will ever happen is another story altogether.

Despite his party effectively kicking the can down the road, Noonan has warned the bill is deeply flawed and may even be unconstitutional – earning him the title ‘minister for banking’ from his opponents.

And those charged with enforcing the law, should it get through the ‘pre-legislative scrutiny’ phase’, have so far signalled they have no desire to enforce their potential new-found powers.

The Central Bank’s new governor, Philip Lane, has said forcing mortgage rates on lenders could deter competition in the market while also leading banks to cherry-pick only the best customers.

Central Bank governor Philip Lane

Central Bank governor Philip Lane

Being handed powers it doesn’t want to exercise will test the regulator’s independence, although proponents of the bill have argued the threat alone could be enough to force lenders down.

Analysts at Davy have also warned capping rates could be self-defeating for the government as it tries to sell down taxpayers’ stakes in the bailed-out institutions.

Much of the banks’ loan books are still tied up in the loss-making tracker mortgages they wrote during the boom years, although the extent to which this is acting as a brake on overall lending varies widely from lender to lender.

Any cut in mortgage rates should in turn lower banks’ profits, accordingly reducing their value on the markets.

This leaves the government in a deeply compromised position as a major bank shareholder, with its holdings in the Bank of Ireland, AIB and Permanent TSB, and the supposed defender of residents who are paying much more than their European peers for their loans.

More than anything, the bill is expected to signal the seriousness of the political intent behind the issue – which may be enough to push any wavering banks over the line and into further rate cuts.