Medtech firms have a year to prepare for new EU rules but the inspectors aren't ready

Manufacturers are concerned that authorities aren’t fully prepared to meet demand.

THE CLOCK IS ticking on a raft of stringent new rules for medical device makers – and there are serious concerns in the medtech sector that inspectors aren’t prepared for the incoming regime.

The EU is set to enforce the new set of regulations, the Medical Device Regulation (MDR), in May 2020.

It introduces more rigorous rules around the clinical data that device makers have to provide to get certified for the market as well as fresh responsibilities for post-market surveillance and incident monitoring of devices.

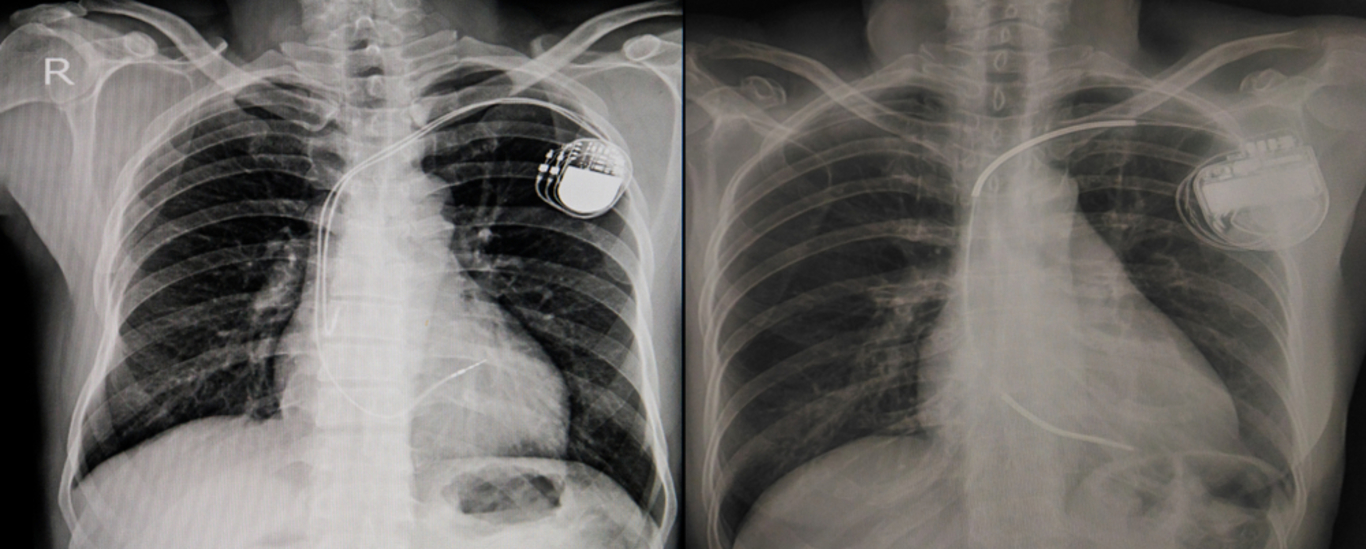

The regime hits everything from pacemakers to joint implants.

It also pulls more products under the umbrella, such as the software that accompanies devices and even extends to cosmetic products like dermal fillers and coloured contact lenses.

The MDR also affects device makers with existing products on the market, which will need to be re-certified.

The updated rules were approved in 2017, giving the industry about three years to get its ducks in a row.

Europe has recently contended with a series of controversies around the approvals of medical devices for the market and their risk to patient safety.

As 2019 commences, medical device giants and startups alike find themselves in the final stretch before the deadline of 26 May 2020. Another set of rules for in-vitro diagnostic medical devices, called IVDR, which commences in 2022, is also on the agenda.

Áine Fox of the Irish Medtech Association said that the industry is investing heavily in its compliance with the MDR framework, but it’s a new frontier.

“They’re quite extensive, they represent probably the most modern and stringent set of rules in the world for medical devices. It’s a whole new ball game here,” she said.

It will be a “critical year” for the industry and could create new hurdles for medtech startups trying to get into the busy market.

“I think it will present a unique challenge for startups,” Fox explained. “Large multinationals have large cohorts of individuals preparing for implementation.”

“As an association, we’re working very closely with our SMEs and startups to ensure that they have access to the relevant training.”

System readiness

The key concern lays around how ready the regulatory system is to certify and approve devices by the 2020 deadline.

Notified bodies are the organisations tasked with certifying devices under the MDR regime. The new rules aim to create greater uniformity and ensure all notified bodies are singing from the same hymn sheet.

The notified bodies themselves need to be re-approved under the new rules in order to certify products for compliance. This means training staff in understanding the laws and putting the resources in place.

To date, no European notified body has been approved under the regulation.

Industry players fear this will create a backlog of applications to certify and re-certify products ahead of the May 2020 deadline – in turn causing delays in getting devices on the market and into hospitals.

“It is a concern because there is uncertainty about when the certification is going to happen,” said Joan Fitzpatrick, chief executive of Galway startup Kite Medical.

Kite Medical is testing a sensor pad for diagnosing renal reflux and will be carrying out trials in Europe and the US.

A spokesperson for the Irish notified body, the National Standards Authority of Ireland (NSAI), told Fora that it is currently in the “process of approval under the regulation”.

It is aiming to get approval from Europe within the second quarter of this year at which point the NSAI will be able to start certifying devices.

There will be some reprieve for startups though as they are not required to use a notified body in their base country.

Fitzpatrick said Kite Medical will likely use the UK-based British Standards Institution, which has established a post-Brexit operation in the Netherlands, or Germany’s TÜV SÜD, given their expertise in mechano-electric devices – the area Kite’s pad device operates in.

Joan Fitzpatrick (centre)

Joan Fitzpatrick (centre)

But the CEO of one Irish medtech startup, that did not wish to be named, told Fora the rules will place a burden on young companies to invest in carrying out more rigorous tests.

“I think overall it will slow down the development and products coming to market in the EU, and generally people are now – particularly in startups – slower to take on the EU CE marking pathway for a truly novel innovative device than they would have been (before),” he said.

He added that the US continues to be the most important market for device makers and the MDR could lead to startups diverting even more attention Stateside rather than Europe.

“The US is a much bigger, more defined market.”

Atlantic Therapeutics, based in Galway and fresh off a €28 million round this week, has had its wearable electrical stimulation device for treating incontinence on the EU market for a few years.

Chief executive Steve Atkinson said its approval in the US from the FDA, which is also a notably demanding system, will inform its strategy for the MDR. It too plans to use the British Standards Institution when it is ready.

However, the issues surrounding the MDR are not just a cause of concern for the small- and medium-sized players.

US firm Zimmer Biomet, which has plants in Galway and Shannon, wrote to the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) last year, which oversees notified bodies, to say the three-year period introduced in 2017 has not been sufficient.

“The tragic thing about the situation is that it has long been clear to everyone that a transition of three years does not work, but nobody feels responsible for undertaking anything,” a Zimmer Biomet representative said in correspondence released under freedom of information laws.

“This situation creates a lot of legal uncertainty to our manufacturing sites and supply chain duties to our hospitals!”

Niall MacAleenan, medical device lead at the HPRA, told Fora that “there is potential for delays in certification to the MDR”.

“It’s certainly something we’ve heard as a big challenge for the system to have an adequate number of notified bodies designated in time,” he said.

MacAleenan added that he expects the first notified bodies in the EU to be MDR-approved by the end of this quarter.

Grace period

One solution is the so-called grandfathering clause. It allows companies a grace period to extend their deadline for certain existing products to 2024.

Manufacturers can use this clause if “no significant changes are made to their device” after 26 May 2020, according to the NSAI.

MacAleenan said that the clause “provides for a softer landing” in some cases, but Áine Fox of the Irish Medtech Association said the stipulation is only a Band-Aid on a bigger problem.

“Unfortunately the safeguard mechanism that this grace period is supposed to represent doesn’t really provide a system-wide solution,” Fox said.

“It’s not sufficient to address what is described as a re-certification bottleneck; 2019 to 2020 will be a crunch period.

“While that is an option, we feel that it is not necessarily a sufficient system-wide solution to deal with any delays that may arise.”