Hype, product delays and a few broken promises – the highs and lows of crowdfunding

Being a success on platforms like Kickstarter often has little to do with how much money you raise.

WHEN IT COMES to the hard data on crowdfunding, the pitfalls are stark. The majority of projects on the most popular platforms are destined to fail, falling short of their targets.

And even for those that succeed, there is plenty left to overcome – a quick glance over the high-profile flameouts of designers who have drastically over-promised makes for sobering research.

But Irish businesses continue to flock to platforms like Kickstarter and many of those who have been on the crowdfunding roller coaster swear by the process – even when they don’t hit that elusive goal.

A flop

Dundalk-based product designer Darren Louet-Feisser is blunt in his assessment of how his device, the Chewy herb grinder, performed on its Kickstarter debut.

“It was initially a complete flop,” he tells Fora.

“We only raised $8,000 of the $30,000 … but it was really all about pre-production marketing for us.”

Although the product he and business partner Ronan Woods were launching fell well short of its target, the accompanying pitch video racked up 200,000 views – and the traction behind the project saw the pair wind up with 30,000 pre-orders.

More recently, the pair were approached by a US agency representing what Louet-Feisser describes as ”high-profile hip-hop artists”, who want to endorse the weed-friendly product.

In the end, the pair needed to turn down the pre-orders to cope with the scale of the US order.

“These guys are estimating we will sell 300,000 units in six months at $100 a unit. Now we have the first 50,000 units in production,” Louet-Feisser says.

The Chewy

The Chewy

Sidestepping failure

Nearly two-thirds of all campaigns on Kickstarter fall short of their funding target like the Chewy, while on other popular platforms like Indiegogo, only one in ten projects are funded.

Irish website Fundit.ie bucks the trend, claiming a 70%-plus success rate, however it operates in a niche area, for creative projects only.

“There’s no way we do it for the money,” says Luke Brennan, the managing director of MyVolts and an experienced user of crowdfunding websites.

“It’s about the coverage you get. If, at the end of a campaign, you know about the products we make, that helps us when we release a new product.

“If you just tell people there’s this product you’re making, no one really cares. After the Kickstarter campaign, however, you end up having lots of people really interested in what you’re doing.”

Nevertheless, Brennan has managed to fund two separate projects - MyVolts’ bedside gadget charger, Z-Charge, raised €44,000, while the Ripcord USB power adapter exceeded its target to hit €28,000.

He says part of the success has come from having a large existing customer base to tap into but also from knowing the kind of projects that will get traction online.

“If you don’t have the ‘that would be cool to have’ factor, people aren’t interested. And if it doesn’t have mass appeal, that will make life difficult as well.”

The next step

But even for those projects that do make the cut and hit the funding goal, delivering on your promises isn’t always straightforward.

Manufacturing headaches, product faults and projects simply running out of money before shipping are all problems that commonly crop up during the fulfillment process – and sometimes the scale of the failures are spectacular.

Last year, one company, Skarp, managed to raise $4 million for its campaign called Laser Razor – before being suspended from Kickstarter when it failed to produce a working prototype.

However it is rare for a project to even be cut short. More often, struggling campaigns are left in limbo as companies scramble to deliver on pledges within budget.

Backers of the $13 million campaign for the Coolest cooler – which set a Kickstarter record with the project - were left hanging for almost two years while only dribbles of their orders came through.

The company suffered numerous shipping delays and ended up selling the final product on Amazon to raise enough money to fulfill the initial crowd-funded orders.

Irish projects, in contrast, haven’t suffered the same kind of high-profile hiccups. But shipping deadlines are often the first thing that falls by the wayside when things don’t go to plan.

David Ingram, the chief executive at Galvanic, says his successful crowdfunding campaign suffered several setbacks that meant the project fell short of its delivery date.

His company had a hit on Kickstarter with a stress-management device called the Pip, which was the first Irish project to hit $100,000 in funding.

The Pip

The Pip

“I don’t know if there is any Kickstarter campaign where there is a product being manufactured and they hit the target date they set,” Ingram says.

“We ended up shipping product in August 2014 and originally it was meant to be March or April. That’s pretty good compared to other challenges I’ve seen people face when they are manufacturing.

“That just reflects real life because things don’t always go according to plan. The key thing is that you keep your backers informed about what’s going on.”

Being up-front

Monaghan-based Benny Magennis, who launched his Whackpack range of handmade wooden furniture on Kickstarter, also had to push back his deadlines – but he learned the answer was to be completely up-front about the delays.

“I did my project in June, finished in July and had August down as my shipping date, which should have been changed before we put it live. I had let my backers know as soon as the campaign ended that it would be two months.

“I’ve found that serial backers on Kickstarter will wait. They are patient with you because they see you’re doing something new and as long as you keep them updated you don’t really piss them off.”

Magennis says his problems revolved around being able to make enough products to ship before the deadline, but anyone who waited until a project was funded to worry about how they would deliver on pledges was playing with fire.

“You definitely do need a plan in place for fulfilling any kind of order before you go down the route of offering something for a price.

“You could go to a courier company and find it costs more than the price of the pledge and then you’re in trouble because you’re losing money.”

Cap in hand

One Irish product designer still in the thick of the manufacturing and fulfillment process is David Craig, who is hoping to get his device in the post in just over a month – three-quarters of a year after he originally planned to be delivering the first batches.

His campaign to crowdfund a new digital styli raised over €66,000, but a few technical difficulties have led to setbacks.

“I’ve taken the whole thing very personally the whole way along,” Craig says.

“Anyone who has pledged money, you feel somewhat indebted to them. We’ve had to go to our backers cap in hand and embarrassed at times and apologise.

“But in some cases the delays have helped because it has allowed us to bring forward functionality we thought we would put off until the second-generation model.

“It’s like an apology from us … now we can offer them something more cutting edge than they originally paid for.”

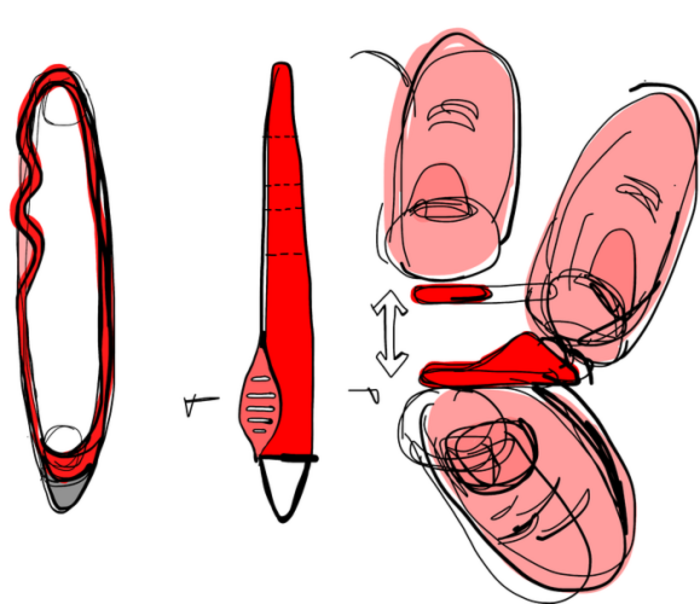

An original sketch of the Scriba styli

An original sketch of the Scriba styli

Feedback from crowdfunding backers worldwide suggests that the vast majority of successfully funded campaigns do eventually deliver on their promises.

A study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania showed that only one in 10 Kickstarter projects failed to deliver rewards and nearly two-thirds of those surveyed felt the reward was delivered on time.

When failure isn’t failure

Regardless of the campaign outcome, the main motivator for most businesses choosing crowdfunding is to create a springboard to bigger and better things.

“If you don’t reach your target, it’s not the end of the world,” says Sinead Geraghty, who tried the crowdfunding route for her bike-storage solution, the Stowaway.

“We didn’t hit our target, but we got so much global exposure and now major distributors from all over the world want to stock our product once it’s ready to go.

“A distributor in Hawaii told me he wants 100 units as a first order and, when the Kickstarter was running, a Canadian guy who is a garage fitter and has a thousand employees across Canada got in touch because he wants to become a distributor.

“For me to find those needles in a haystack by myself would have taken forever.”

The Stowaway

The Stowaway

Still, Geraghty says the only reason she was reaping any rewards from the campaign was because of the time she put into marketing the product.

“A lot of people underestimate it and just think if you put your project up it will be found. But there are so many projects on Kickstarter at any given time and you could be at the bottom of that ranking. And like Google, nobody goes past page two on Kickstarter.

“You have to figure out who the influencers are going to be – bloggers, groups and journalists – to get a following behind you before you even launch. Then even when you launch you need to be there constantly to answer questions and comments from users.”

Lead-in time

Depending on who you ask, the time that should go into a project before actually pressing the go button on a crowdfunding campaign ranges between six months and a year.

“We were planning for eight months, but I think I didn’t plan enough,” Magennis, of Whackpack, says.

“If I was doing another crowdfunding campaign, I would network for about a year telling people it’s coming.”

Benny Magennis in his workshop

Benny Magennis in his workshop

But building that hype around a launch can also be an all-consuming job, those who have been through the process say.

For Ingram and Galvanic, the project quickly ended up a major distraction as managing the crowdfunding campaign became staff’s sole focus.

“A small company will effectively have to down tools,” he says.

“We had to do that even though we put a lot of work into the project in advance, like perfecting the video pitch and getting the pledges right.

“We had six people in the business and everybody was involved in pushing and assisting in it.”

Key to success

But the flip side to sinking valuable man hours into a project is the chilling effect a lack of hype can have on a campaign.

For the Chewy, designer Louet-Feisser admits his business probably didn’t dedicate enough time to building momentum pre-launch.

He learned quickly that a project which failed to bring in an initial surge of supporters and funding was probably doomed to fizzle out. Those which attract quick surges of support generally feature more prominently and can earn Kickstarter’s coveted ‘staff pick’ endorsement to give them extra impetus.

Wyldsson managing director Dave McGeady ran a campaign to fund a new healthy snack product, hitting the target of €5,000 within 24 hours and ending with more than €10,000 in pledges.

Dave McGeady of Wyldsson

Dave McGeady of Wyldsson

McGeady says the key was being able to draw people to the crowdfunding platform, rather than relying on catching the eye of a casual browser.

“We have benefited from people stumbling across our project, but that wouldn’t have filled out the campaign,” he says.

“We have quite a large customer base and were able to just email them about what we were doing and hit our target quite easily. Ordinarily, you probably won’t have that customer base and you need to go out and hustle.”

But Louet-Feisser says measuring the ultimate success of a crowdfunding campaign comes down to a lot more than view counts or even pledges.

“Kickstarter is just pre-sales. If we raised $2 million, that would have been great – and I would prefer to be able to say we raised millions.

“But even if we got a million dollars on Kickstarter, it would not compare to what’s happening for us now.”