Your crash course in... Why slashing a country's credit rating matters

The UK had its AAA rating downgraded in the wake of the Brexit vote.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF a likely Brexit have come raining down on Great Britain since the country voted to leave the EU last week.

Multinationals, such as Vodafone, have hinted that they may relocate activities to avoid the economic turmoil, the pound plunged to a three-decade low and the country had its credit rating downgraded.

So for the week that’s in it, we’re going to focus on the last point – the slightly opaque world of credit ratings – and look at why anyone cares.

What is a credit rating?

A credit rating can be summed up as an assessment of the risk associated with loaning money.

For example, let’s say your friend Kevin wants to borrow some cash from you to buy a bag of crisps, you might want to know how likely you are to get the money back.

You asked around if Kevin is good for the money and people told you he has recently invested all his money in DVD rental stores and cloud insurance.

Armed with the information that Kevin is making some poor investment decisions of late, you might want to charge him significant interest on the money you lend to him to make up for the risk of not getting it back.

The system works in a similar way when it comes to countries borrowing billions of euro – rating agencies exist to help you work out how likely it is you will get your money back.

Who decides a country’s credit rating?

Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Fitch Ratings are recognised as the three big hitters when it comes to credit rating agencies. If these three private companies decide to cut a country’s credit rating, it normally makes the headlines.

The three firms are all over 100 years old with headquarters in New York, but Fitch also has a centre of operations in London. Between the three of them, they command 95% of the global credit ratings market.

Their dominance can also be attributed to the fact they were the first credit agencies to get the stamp of approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission, which is the overseer of the US financial sector.

Although credit rating agencies are seen as the benchmark-setters for judging financial risk, people might be more inclined to take their assessments with a pinch of salt after the financial crisis.

The big three credit rating agencies have been widely criticised for awarding many of the US banks and their toxic books of sub-prime mortgages with the highest ratings in the lead-up to the crash.

How does the scoring system work?

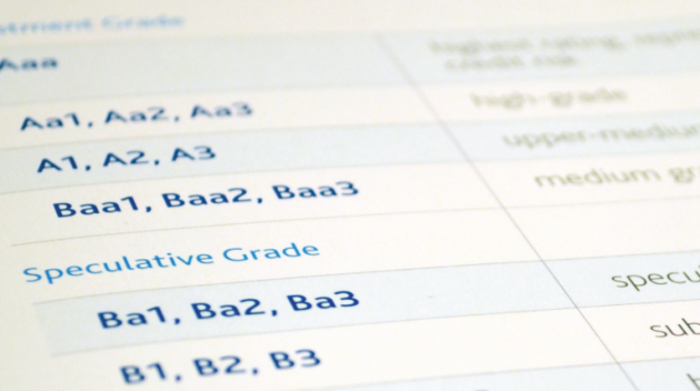

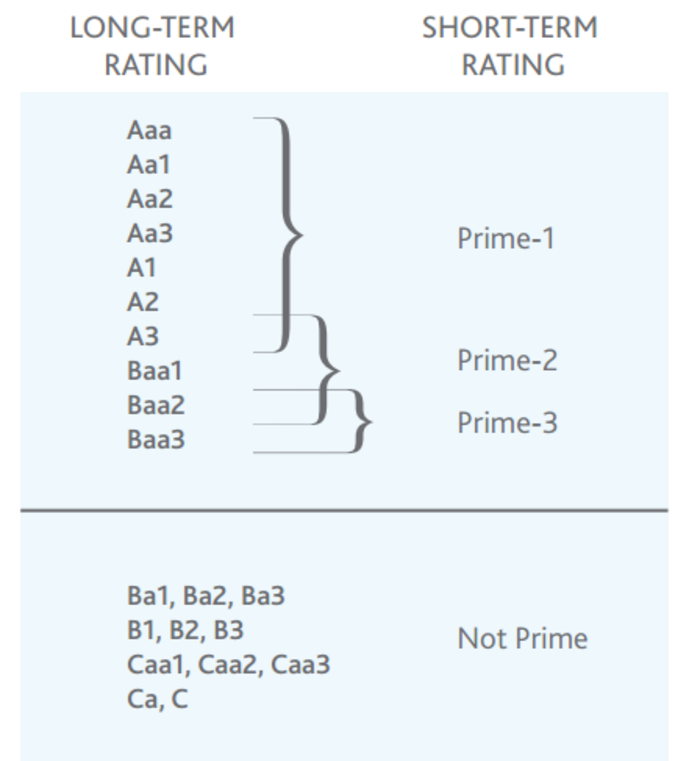

The system has a number of different scores which range from a top credit score of triple-A (AAA) to the lowest D, which also means ‘in default’.

Between AAA and D, there are other scores such as BB and C. For example, Great Britain’s credit rating under Moody’s standards is Aa1, which is the second-highest rating.

In addition to credit ratings, the agencies also provide outlook assessments. Countries can fall into the ‘positive’, ‘stable’ or ‘negative’ categories, which indicate whether the agencies think a country’s credit rating is going to rise, fall, or stay the same in the near future.

Moody's credit rating scale

Moody's credit rating scale

Click here for a larger version

Why does it matter?

The higher the credit rating, generally the easier and cheaper it is for borrowers – whether they’re companies or governments - to attract investment when they sell financial products like bonds.

So in the situation of a country’s government, a low credit rating usually means a hefty interest rate attached to its loans - which can in turn take billions from the bottom line of a budget.

That means less money that could otherwise have been spent on improving hospitals or roads, and often higher taxes to make up for the shortfall.

Conversely, countries with high credit ratings are perceived as being the lowest-risk investments and enjoy the cheapest borrowing costs.

Germany, one of the gold standards when it comes to government bonds, has a triple-A credit rating and can currently borrow money for all but the longest periods at negative rates – meaning people are effectively paying to lend it money.

German chancellor Angela Merkel

German chancellor Angela Merkel

Why was the UK’s credit rating slashed?

It won’t come as a surprise, but it’s all because of the Brexit result. The aftermath of the referendum has brought with it a bucketload of economic uncertainty in the country.

Moody’s was the first to make a call, cutting its outlook for the UK from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’. It said the outcome of the referendum would result in “negative implications for the country’s medium-term growth outlook”.

The agency also said Brexit will “reduce the profitability” of 12 UK banks and building societies and “lead to lower GDP growth over the next two years, in response to diminished confidence and lower spending and investment”.

Meanwhile S&P downgraded the country from a Triple-A (AAA) rating to the second-highest rating (AA) and said the referendum outcome was “a seminal event, and will lead to a less predictable, stable and effective policy framework in the UK”.

Fitch, the other notable credit ratings firm, gave Great Britain a credit rating of AA with a negative outlook and slashed its economic growth forecasts for the country over the next two years.

Leave campaigner Boris Johnson

Leave campaigner Boris Johnson

Will Ireland’s be dragged into this mess?

Based on rumblings out of Fitch, it looks like Ireland will be spared any Brexit backlash… for now.

Under Fitch’s system, Ireland has an A rating (the third-highest score) and a stable outlook. Basically it means Ireland’s credit rating shows no sign of changing any time soon.

Ireland has a very similar future in the eyes of S&P, with a credit rating of A+ and a stable outlook, while under Moody’s system the country has a rating of A3, the fourth-highest ranking, which could increase again very soon.