As farm incomes dwindle, getting farmers to embrace technology is a tough sell

Many agribusiness owners are more worried about learning to use smartphones than the latest gizmos.

FARMING TECHNOLOGY HAS the power to boost the profitability of cash-strapped agribusinesses, but it remains a tough sell for struggling producers who need more than incremental gains to shore up their bottom lines.

Small gadgets like the Irish-designed Moocall can alert beef and dairy farmers when a calf is being born, taking away the labour-intensive job of checking a herd multiple times each night.

At the other end of the spectrum, large-scale machinery developed by Carlow-based Keenan uses cloud-based technology to mix feed ingredients for livestock.

However James Murphy, who heads up the Irish Farmers’ Association’s (IFA) work on renewable energy, among other areas, said it was hard convincing farmers with scant profits to buy into technology – even if it could streamline their work.

“There isn’t a huge amount of proof that using high-level technology adds profit to a farming enterprise,” he said.

“On the grain side, those guys are more high-tech and they are spreading fertilizers to within an inch of accuracy, but they’re going to lose their shirts off their backs this year due to poor profits.”

Irish farms remain heavily reliant on EU subsidies to turn a buck, despite the average farm income increasing by 6% last year to around €26,500, according to the latest Teagasc National Farm Survey.

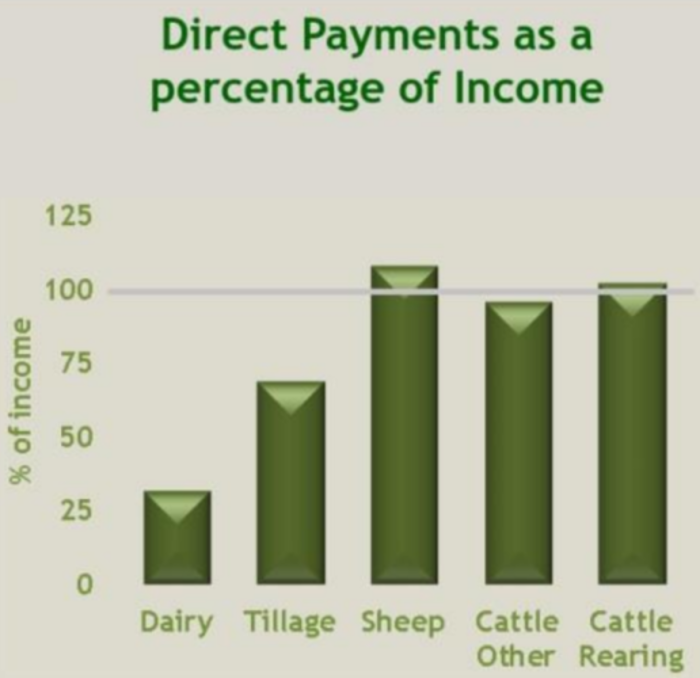

In some sectors, state-supplied ‘direct payments’ make up more than 100% of the average farm’s income, meaning they would be operating at losses without the support.

Murphy added that a lot of farmers have become resistant to technology because it has been forced upon them.

“Farmers are resisting the opportunity to use tech because they would rather stick at what they’re doing. Technology is adding costs to farming systems that at the moment don’t have a margin to add that cost.

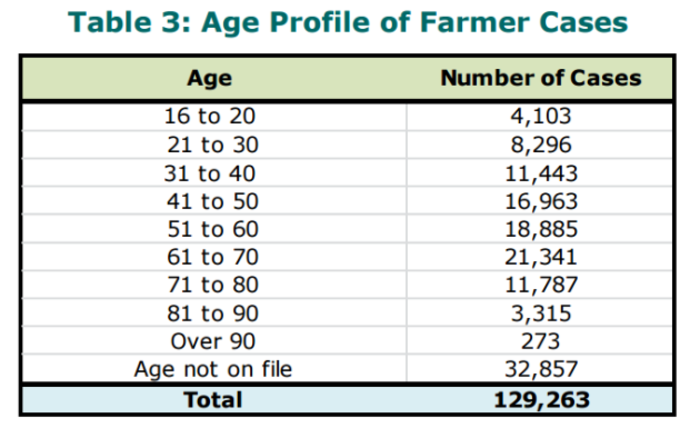

“If you look at old farmers, they are still on the old Nokia and most are unfortunately the wrong side of 55, so there isn’t a great willingness to go back and relearn the skills.

“When farmers can’t see profit or a real benefit to adopting tech, they end up resenting technology they are made use, like the (smart) sheep-tagging system and being forced to make applications to the department online. Most guys can’t do it. They have to pay a third-party to do it for them, which adds more costs.”

Even if tech can take some of the mundane tasks out of farming, Teagasc economist Kevin Heanue said a poor cost-benefit ratio is often one of the main factors turning farmers off using more technology on their farms.

“Farmers are no different to any other businesses in their approach to adopting technology. They look at how it can improve performance and what is the pay off for that improved performance,” he said.

Key to adoption

Nevertheless, when technology is easy to implement and comes with a clear benefit, getting farmers on board is not a hard sell, Heanue added. These were the key factors that companies developing agri-technology needed to keep in mind.

“A lot of technologies that farmers use, like AI breeding, are highly scientific, but the ease of implementation of this technology is crucial to adoption. If it’s free from effort they will use it.”

Keeping the user’s experience of the technology as straightforward as possible has been key to the success of calving alert system Moocall, according to the company’s chief executive, Emmet Savage.

His business has received significant investment from businessman Michael Smurfit, the Irish Farmers Journal and others.

“We have farmers in their mid-70s and 80s down the west of Ireland that don’t even have a smartphone, but they can use our product,” Savage said.

“The guys don’t need to know how technical the product is behind the scenes. All they want is an uncomplicated user experience and we have created that with the knowledge that a lot of our customers are not technically savvy.”

Moocall CEO Emmet Savage

Moocall CEO Emmet Savage

Eddie Daly, an account manager at Keenan Intouch, which develops high-tech animal feeders, said a lot of young farmers who received third-level education are less reluctant to use the latest machinery, but to make the sale to older farmers you need to work hard to prove the benefits.

“Seeing is believing and farmers are slow to uptake technology and getting them over the line is about showing them the profitability,” he said.

“But even though they might be skeptical, we still see up to 500 farmers at our open days because of curiosity.”

The IFA’s Murphy has seen this curiosity first hand. He said a lot of farmers might give off the impression that they are technophobes, but once their interest is sparked, they will make the effort to learn about new gadgetry.

“Where farmers can see a real benefit, they are open to moving to new technologies. The next generation will find technology the norm, but for the guys of today, they’re a lot more reluctant to even trust these technologies.”

Trust issues

Gaining that trust is another key issue, particularly in getting potential users to trust that the tech won’t let them down when they need it most.

Teagasc regularly holds local discussion groups to get farmers to pool their knowledge and advocate for equipment they use, which also breaks down a lot of barriers for farmers resistant to adopting new technology.

Murphy said farmers learned best from their peers because they were likely to trust that what worked for their neighbours will also work for them.

A cow fitted with a Moocall monitor

A cow fitted with a Moocall monitor

Nevertheless, much of the IFA’s work when it ran technology courses for farmers was far removed from the likes of drones for sheep-herding or robotic machinery.

Murphy said the organisation was often more focused on teaching members the basics of using smartphones, email and internet banking.

“I am always trying to convince farmers to upskill in tech, but the interest isn’t always there. You will get them into a sheep-dog training course, but it’s much more difficult to get them energised about technology-type course.”